Read this on Medium or below.

Installation about forests & changing seasons in the Groote Museum, Amsterdam

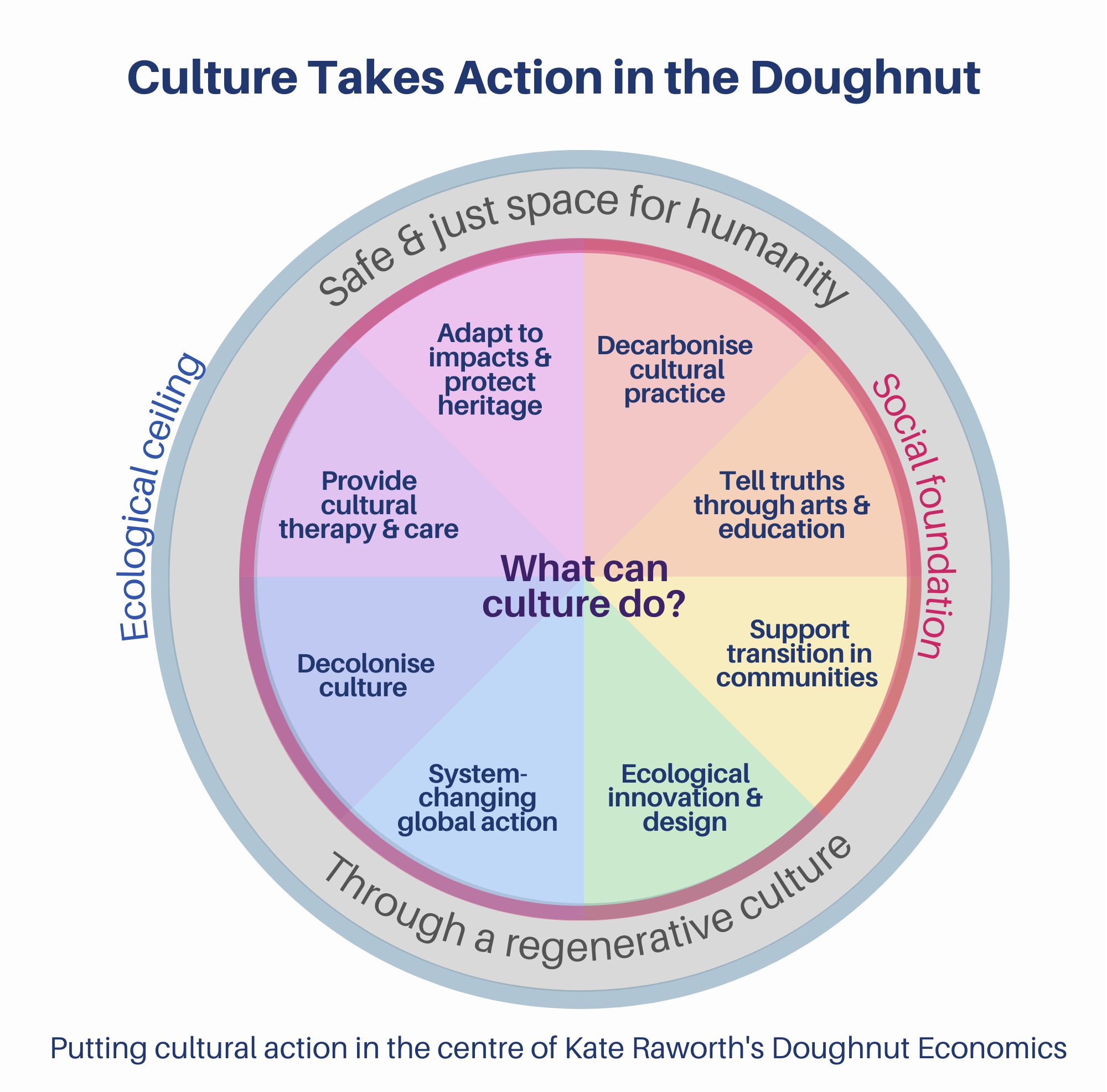

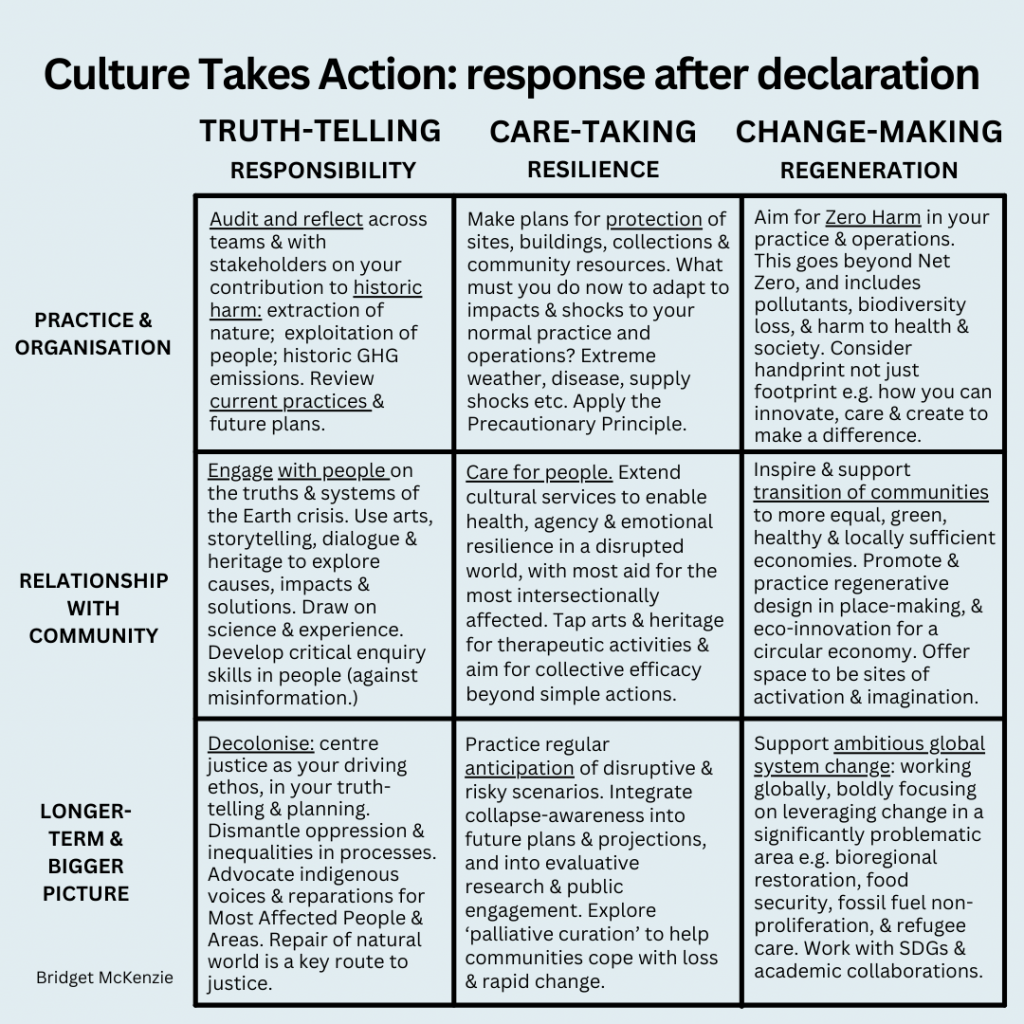

This is an attempt to get an overview of the different ways that museums can respond to the Earth crisis. There are many ways to cut and slice this, as I have done in the past. I’ve written many frameworks, calls to action and manifestos for the cultural response to the crisis over the past 17 years. See the most recent, which includes a re-making of the Culture Takes Action framework. It’s structured around three pillars: truth-telling, care-taking and change-making.

For this article, I wanted to use these pillars to focus on museums, rather than culture in general, and to represent what I’ve seen some doing already, rather than to exhort them to start doing these things. In each pillar, there’s one type of action that is expected or common, and another type of action that is much less common and more of a stretch.

For now it’s a simple list. Ways to develop it could be:

- To add case studies of good practice. (If you’d like to share any, please comment here, or get in touch on bridget.mckenzie@flowassociates.com)

- To find other categories of response, from niche outliers to significant unconsidered areas of work.

- To test and develop my theory that these are the six main areas, in three pillars, of response. This might include exploring the ways that sector practitioners have different perspectives in different international contexts, or finding different terminologies or approaches for work in these categories, or different ways they are combined or connected.

- Drilling down into one museum, heritage site, or group of museums in one place to explore the possibilities of these six areas of action.

TRUTH-TELLING

Environmental content

Using the assets of museums to engage people, including:

- their authoritative reputation, particularly in the case of specialist or national museums

- their relationship to places, enabling contextual meaning-making for local communities, particularly in the case of regional and local museums

- their collections, drawing on aesthetic, technical, scientific, spiritual and historical resonance

- their spaces, affording people to gather, potentially to feel safely abstracted from life’s pressures or limits and able to connect with others differently, and affording the design of narrative experiences

- their people, offering expertise in subjects, collections and methods of interpretation and creative dialogue with different communities.

Different types of museum might generate environment-related content in the following ways:

- General or mixed collections: Putting an environmental lens on artefacts, very often using a place-based story to make this meaningful; connecting natural & cultural collections to explore changing places over time; environment as a hook for eco-concerned visitors.

- Art museums: hosting contemporary artists who work on environmental themes e.g. land art, recycled art, or (less frequently) activist art; platforming indigenous artists, who may work in contemporary modalities or traditional & more collective, or a mix of these; critical & environmental interpretations of collections such as landscapes & seascapes.

- Museums of science and technology: histories of climate and environmental science; a focus on discoveries and evidence e.g. to reinforce proof of AGW against denialism (which is tricky on occasions when sponsored by fossil fuel companies); providing basic knowledge to enrich the curriculum to ensure future citizens are equipped for a green transition; promoting technical solutions, often supported by companies or national programmes. Industrial heritage sites might reflect on the contribution of this industry to environmental harm, and the potential solutions.

- Natural History museums: more political, contemporary or critical interpretations of biological sciences and specimens than previously; putting their specimens in a wider context of Earth systems and why they are disrupted e.g. species migrations affected by climate disruption; using geological collections to offer a deep time perspective on climate change and species extinctions.

- Outdoor museums, natural heritage sites and gardens might have specific responses that could be explored too.

It is helpful for museums to reflect together as a whole team about their ethos and approach to the Earth crisis. This might follow an internal truth-telling process, perhaps signing up to declare a climate and ecological emergency and reviewing your mission and practices in the light of this.

Critical discourse and systemic analysis

I’m suggesting this is distinct from ‘environmental content’ because it’s not generally surfaced in displays but in more academic platforms such as publications or conferences, or in closed community contexts. Alternatively put, it might not be as simple as offering entertaining stories or interactives in order to shift people in attitudes and behaviours. It is more about interrogating complexity and nuance. We should in future see more of this extending into public engagement.

It might be about exposing your internal processes of truth-telling, and working through them with your visitors and stakeholders. (See the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts in their curating of climate change in context of colonial histories, as an example.)

- Collecting and exploring petrocultures, consumerism and ‘everyday ecocide’ — e.g. examining the construction of cultural discourses that perpetuate extractive capitalism and its means of living.

- Processes of imagining and analysing future scenarios, using museological assets to do so — e.g. looking deeper into the past or into alternate realities of hypothesised histories. Or sharing alternative framings of large systems and futures e.g. Afro Futurism and Queer Ecologies.

- Centring voices and practices of indigenous, displaced or exploited people — e.g. to examine toxic heritage and political ecologies.

- Illuminating the links between colonial histories of museum collections and the extraction of resources and artefacts from lands and communities. (Noting that from a Western perspective they are seen as resources or artefacts, whereby in context they are seen as integral and sacred elements of life).

CARE-TAKING

Practical adaptation

Adaptation is a series of ongoing adjustments to a changing context, particularly the severe and uncertain impacts of climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution (and related human health impacts, mass migrations and conflicts). Areas that museums are, or should be, considering include:

- Making adjustments to account for increasingly straitened circumstances — price rises and shortages of food, energy, materials and travel. Increasing displacement, racism, polarisation and conflict. Community engagement projects addressing these challenges, using the museum’s assets.

- Dealing with extreme heat, storms, floods, pests & diseases and other climate risks. Anticipating and planning to minimise effects on collections and visitors, and in the longer-term and in extremis how they threaten livelihoods, staff wellbeing, tourism and the cultural economy.

- Dealing with global pandemics and other severe impacts on human health with environmental causes, such as air pollution, and considering both the immediate and longer-term impacts, as above.

- Drawing on the assets of museums to support wider civic efforts at adaptation in bioregions, cities and sectors.

Palliative curation

This term was introduced by cultural geographer, Caitlin DeSilvey. Palliative care is supporting patients and family on a terminal pathway. The word ‘curation’ is related to the word ‘to care’ and means stewardship or guardianship of heritage. Palliative curation involves communities in supported processes of saving what can be saved, slowing down the loss, or letting go of their knowledge, of their valued life-ways, sites and artefacts in the face of loss or damage. Museums might carry this out in the following ways:

- Documenting, protecting and restoring material and site-based heritage harmed by development, pollution and climate impacts.

- Collecting and interpreting heritage related to the seasons & interactions with nature in the stable climate that has given rise to human civilisation, and comparing it to the disrupted climate we’re now experiencing. Anticipating future disruptions and planning how to protect heritage.

- Capturing and giving platform to experiences of extreme weather, displacement, ecocide and extractive industries affecting place and heritage.

- Cultural therapy for eco-anxiety, displacement trauma and environment-related illness. Supporting particular vulnerable or intersectional groups impacted by the Earth crisis.

- Creating virtual sites or archives of a community’s heritage after displacement or loss. Offering alternative sites to access Traditional Ecological Knowledge.

- Expanding the museum to see the world as a site of loss (and of potential regeneration), appreciating what is in places and the world. Recontextualising items into place, rather than (or, as well as) extracting them into a museum.

- ‘Reworlding’ — helping to recreate or restore places (including e.g. relationships and economic systems) after destruction or loss, in ways that improve on what was there before, or are more adaptive to changing circumstances.

CHANGE-MAKING

Practical mitigation

- Assessing the footprint of an organisation across all areas of impact: GHGs, other pollutants, biodiversity loss, and harm to health and society. Looking at all the externalities of food, energy, transport, materials, waste, land use and attitudes.

- Implementing ‘Zero Harm’ policies and actions to fulfil your environmental responsibility across the footprint.

- Working with local communities and councils to transition to greener, safer, more healthy environments.

- Innovating in ways of mitigating footprint appropriate to museums and heritage sites, and sharing this practice with peers and audiences.

Being sites of activation

Like ‘palliative curation’, this is one of the more important areas of action, and the most challenging for museums to do given their dependence on funding from governments and corporations that uphold the harmful economic system. Some museums are more independent and therefore more able to act to restore and protect their wider environment, in turn to sustain themselves and the heritage they care for.

- Acts of subversion or critical interpretation that expose museums as perpetuators of systemic harm, not just historically but in the present day. (Radical emerging museums are more likely to carry out such acts, but more established museums might tolerate or commission them.)

- Community-led museums defending their heritage, identity and land in face of loss and damage. For example, a museum might use its assets to explain and campaign against a harmful infrastructure project, or the harmful food or water system affecting local people’s health.

- Eco-museums — a distinct genre of museums — having an overt role to support their local community and biodiversity, generating income and educating people, supporting eco-tourism and sustaining heritage crafts.

- Museums offering space to be a forum for activist groups, and representing activists so that eco-concerned visitors feel reflected and encouraged.

- Using the authoritative idea of ‘museum’ for creative acts of subversion (e.g. a protest that creates a ‘museum of greenwashing’).

- Commissions and residencies of innovative designers or youth-led design thinking, generating new materials, products and solutions for a circular and regenerative economy. Integrating this with retail and sponsorship / fundraising activities.

- Cultural gardening or artful rewilding; seeing restorative or regenerative art and design as the most significant contemporary artforms, where healthful soil, cleaning rivers, large-scale planting projects or permaculture gardens are the new media.

- Museums rewilding themselves, their buildings and grounds, and inspiring their communities to do the same. (For example, the Natural History Museum in London is creating new gardens and the National Education Nature Park across the education estate in England.)

- Museums as agents for tackling ecosystem depletion and species extinction. e.g. running participatory citizen science projects.