…or of ‘nature’, ‘biodiversity’ or ‘ecology’.

“If we are to treat the world (and ourselves) better, we must first ask, how can we know what the nonhuman realm is truly like? And second, if one gets a glimmer of an answer from there, how can it be translated, communicated, to the realm of humanity with its courts, congresses, and zoning laws? How do we listen? How do we speak?” Gary Snyder, Conference on the Rights of the Non-Human, California, 1974.

Although Snyder was ahead of his time in asking these questions, coming to the fore now 50 years later, notice the assumed distinction between humanity and the nonhuman realm, as if they are two different worlds.

“The focus on politics, economics, and law are all destined to fail because they are based around humans. They’re designed to guide humans, but we’ve left out the foundation of our existence, which is nature, clean air, pure water, rich soil, food, and sunlight. That’s the foundation of the way we live and, when we construct legal, economic and political systems, they have to be built around protecting those very things, but they’re not.” David Suzuki, ‘Is it too late to escape the climate catastrophe?’, July 2025

Although Suzuki is right to point out what we’ve excluded, notice that his only reference to the potentially trillions of other species of life is the word ‘nature’.

Does communication to engender care of the more-than-human world (or ‘living planet’) need to be anthropocentric to gain attention? Will people switch off if stories start with cyanobacteria or the distribution of seeds, rather than a human eco-hero? Or are we missing a trick in not fully appealing to the essentially nature-connected animals that all humans already are?

OR, is that task of appealing to our animal natures actually all about being anthropocentric?

When we advocate for ‘river’, ‘ecology’ or ‘biodiversity’ are we only gesturing abstractly towards an idea, creating ever greater distance between our human feeling bodies and the entangled community of sensing beings and elements that we might call ‘nature’?

Ann Light, in her new paper about participatory methods for engaging people with the more-than-human, writes: “Indeed, this work is powerful when it moves away from involving the individual non-human to approach the non-hierarchical, fluid worlds of ecology, and when humans are facilitated to encounter non-human forms as an ecosystem, either literally or through role-play, and immerse in what is to be learnt.” ‘More-than-human Participatory Approaches for design: Method and Function in Making Relations’, July 2025.

Yes, this rings true. I’ve seen so much engagement or activism simplistically educating or advocating for nature via single endangered, iconic or charismatic species, often represented out of context. On the other hand, don’t people engage more empathetically if they can zoom in and consider one non-human species or have a single close experience of one place or being? Doesn’t this help us know ourselves as entangled animals as a foundation for approaching ecology more widely and abstractly? Maybe what is vital is to design for movement:

- from embodied sensitivity with our animist and animal natures

- and then outwards to making cognitive sense of entanglement,

- and outwards again to support stewardship and activism

- …which has to stretch to how dominant structures of ‘power over’ are creating ecocidal violence?

What do I mean by our ‘animist and animal natures’? There’s a cartoon where God reveals his latest creation, ‘Man’. Lucifer gets expelled for quipping, “That’s just a monkey with anxiety”. We are erect apes with time-machine brains and a wonderful/terrible ability to make and destroy worlds. Our success as apex predators, reproducers and creators has generated huge riches and great suffering, especially as key groups (men, white people, people with weapons and compelling stories) have exerted ‘power over’ indigenous people and wild beings. However, the majority of us continue to love and nurture other humans and species, to carry out small acts of daily subversion against the ‘power-over’ narrative, and to feel gratitude for the beauty and sustenance of the living world.

The BBC’s Human programme, presented by palaeoanthropologist Ella Al-Shamahi, explores how Homo Sapiens learned from several different human species and groups, and by adapting through climatic changes and migrations. This adaptive learning has been both aggressive and nurturing. We are shaped by our symbiotic past, including our interactions with viruses, our consumption of different plants and our observations of animals. When I posted on social media about the Human programme, Glenn Albrecht shared his article ‘Vestliens’, where he describes humans as composed of vestiges of inherited microbial organisms. He advocates for Symbiosis rather than Darwinian evolution to understand the becoming of beings. “The new metaphor is the opposite of isolated entities competing ‘red in tooth and claw’, [it is] more like organically unified Russian matryoshka dolls, with tightly nested, but morphologically different entities that are symbiotically connected to each other over deep time and space.”

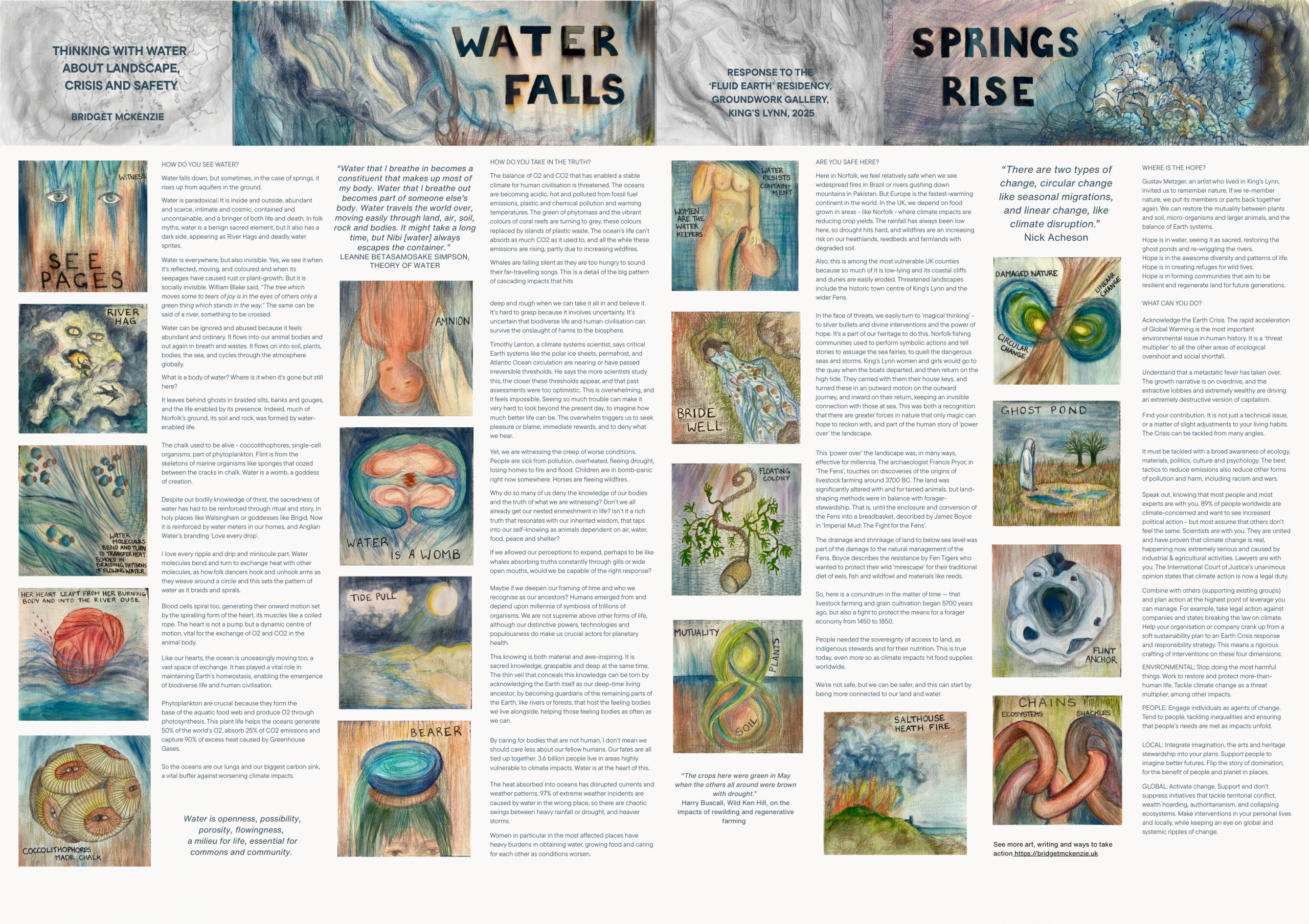

This nested enmeshment makes sense to me as a wonderful idea (and reality). Is it too difficult for many to understand? I try hard and often fail to communicate complex ideas but I can succeed when disbelief, organisational limitations or groupthink are suspended. I did the diagram, above, this week to convey the ideas that:

- ‘The environment’ is not a topic, it is our sacred living world (which is in trouble).

- The environment is not outside of human issues, it is MORE THAN human issues.

- Every issue has an environmental dimension, which is not a small part, but is usually bigger, older, deeper, longer-lasting, more global, more encompassing or more significant than other dimensions.* (Some might argue the spiritual dimension is bigger than the environmental dimension but I suggest they are the same thing. The environment is both material and spiritual, and more-than both.)

- Humans emerged from and depend upon millennia of symbiosis of trillions of organisms, including earlier humans.

- Humans are not supreme above all other forms of life, but their distinctive powers, technologies and populousness mean that we are crucial actors for planetary health.

Don’t we already all understand this nested enmeshment? Isn’t it a rich truth that resonates with our inherited wisdom, that taps into our self-knowing as animals dependent on air, water, food, peace and shelter? This knowing is both materialistic and awe-inspiring. It is sacred knowledge, graspable and deep at the same time.

The standard view in environmental communications and cultural public engagement is: ‘simplify’, ‘’use shorter words’, start where people are’, and ‘tell a human story’. I disagree and yet I agree, and get tied up in knots. I usually start a bit deeper and wilder than where most people are assumed to be, and find that most can be happily drawn in with provocations or stories that feel a bit weird or knotty. Mostly, I work best with children or non-experts, who don’t block proceedings with questions like, “nice, but, is this realistic?” or “won’t this be too difficult for normal people?”

How do we tell a bigger story, beyond the narrative of humans going into nature for our well-being and wealth?

I went to see the film, Rave On for the Avon, a brilliant celebration of swimmers campaigning for clean water access to the River Avon. I was moved by the human stories (the scientists, the mermaid, the carpenter…). However, I was shocked by how human-centric it was. We could see trees, and, once, a heron. There was mention of an otter. A Mum explained that weed is a sign of a healthy river. But that was it. The camera did not dip below the surface or explore the edges. When artist Meg married the Avon, the ceremony text included the “wider river community”. I thought, ah, at last, we’ll hear about the waterfowl, insects and fish, but those listed were cyclists, fishers, walkers and kayakers.

The group of young women scientists met with a man from Wessex Water who smirked while saying that it was only humans affected by the sewage, that ‘the ecology’ could deal with it. The film could have properly addressed this lie, this grouping of all feeling inhabitants under the title of ‘ecology’. It was a chance to expand from the campaigners’ focus on poo-and-humans to point to other pollutants such as pharmaceuticals, fertilisers, or industrial chemicals like mercury & cyanide. And the impacts of climate change such as salination, or how evaporation concentrates pollutants. Someone in the film said the focus on sewage and swimming was a gateway to engagement, around which other building blocks could be added. But we never heard what those other building blocks could be.

I’ve made a strong critical point about this film precisely because it is so good. Such effective vehicles need to go a lot further.

Rob MacFarlane recently launched his new book, Is a River Alive? My response to this question was a wholehearted YES, from the part of me that loves metaphor, and wants wild places and species not only to be seen but prioritised and restored. The semantic pedant in me knows that a river is a milieu that enables life. It is lively, and not a sentient animated body in itself. But I think this is a good tension, that both the sacred and scientific dimensions can co-exist.

I’ve discussed how we need to move people from a focus on wild beings as feeling bodies like our own, towards a bigger understanding of the political-ecological system. This is a huge stretch. What kinds of experiences can be a tightrope for people to walk between those two poles? What can be concretely accessible to a community while also conveying the interconnectedness and troubled nature of our ecosystems? For some communities, there isn’t a better answer than River Guardianship, coming to recognise a river as a lively body with rights to exist, persist and thrive. The same can apply to a forest, a moorland, an urban patchwork of green spaces and so on. My stretch challenge to place Guardians is to recognise each of its inhabitants as having those same rights. And, beyond this, to observe and ask these inhabitants what they need.

I think that the breaching of Planetary Boundaries means we must challenge the framing of balancing human needs with biodiversity, as if one species has an equality of rights with trillions of others lumped (or ‘othered’) into a concept. On these weighing scales, human needs are always the counterweight, the big lump that everyone understands compared to the many featherlight weights on the other side that can be dismissed. An ecocentric approach advocates for seeing biodiversity and ecosystem health as a whole system, with feeling beings nested inside and generating the system dynamically.

The problem is that this sits in impossible tension with an industrial & agricultural system that treats nature as a resource for human destruction and consumption. This traumatised and trauma-creating system prefers nature and its inhabitants to be less alive, less feeling, and in fact, very often, better dead. This framing dominates when decisions are made. The nested wholeness of biodiversity is diminished in various ways — to a numerical measure, a frustrating duty, or a factor of potential some-time benefit to humans. When one species is identified as important, it is often vilified, the pesky endangered ones that stop their roads or marinas being expanded, that is, in countries lucky enough to have nature protections written in law. In Norwich, the Western Link Road across the Wensum River valley was not approved because it would cause a large number of environmental harms, but the pro-road lobby and local paper insist on blaming the Barbastelle Bat.

In a previous post, I’ve supported the IPBES promotion of a Pluricentric approach to nature. This is how I defined it there:

Pluricentric: thinking from multiple perspectives including both ecocentric and anthropocentric. It can also involve shifting between different human cultural perspectives and different types of non-human species — acknowledging racism and species-ism. Being pluricentric requires shifting your gaze, zooming in and out, and being subjective and objective.

I want to edit myself now. There is a benign definition of the anthropocentric and an extractive definition, and no beneficial pluricentric approach to nature would tolerate the notion that human needs are to consume wastefully to grow national extractive economies. A benign definition of anthropocentric is for people to know themselves as animal, with extraordinary intelligence that allows us to empathise and imagine the feelings of others, knowing our well-being depends upon a thriving biosphere.

I stand by the idea of gaze-shifting, learning how to zoom in and out to see tiny parts and vast wholes, travelling in time from deep time to deep future still holding the crux of the present moment in mind. It is about acknowledging the Earth itself as our deep-time living ancestor, and the parts of the Earth (such as rivers or hedges) that host the feeling bodies we live alongside, and to help those feeling bodies as often as we can.