I took part in a Twitter conference organised by ICON’s Sustainability Network, about climate, sustainability and cultural heritage. I tweeted about how the time for sustainability was 40 years ago, and a slightly fuller version of my piece is below.

I’m using this conference to put out fresh thoughts and provocations on the scale, complexity and nuance of challenges that face the Museums & Heritage sector in context of the Earth crisis. The crisis, including climate breakdown, threatens everything we cherish.

The time for declaring emergency and working for sustainability was 40 years ago. Now our sector must focus on being collapse-aware, to aim for ruggedisation and to build a regenerative culture. I’ll explain my terms, defend my provocations and describe briefly what this work might look like.

The first explanation is about being collapse-aware. This means anticipating, facing and responding to the linked crises of ecological and climate breakdown, pandemics, rising inequalities, displacement, famines & conflict. This is what I call the Earth crisis, for short.

The latest IPCC report warns that rising emissions could soon outstrip the ability of many communities to adapt. However models informing this tend not to account for the uncertainties of how climate breakdown intersects with other factors such as deforestation or zoonotic diseases.

I don’t mean that being collapse-aware is about giving up on mitigating harms and emissions, or about being apathetic in face of baked-in emissions & tipping points. I mean being informed about science, for example, about research into how impacts of breached planetary boundaries intersect with each other.

Also being collapse-aware is about awareness of social collapse. In co-operative societies their response can be mainly motivated by mutual aid — ensuring the wellbeing of the majority. This speeds and smoothes the path to recovery, peace or safety. Where society is competitive, where there is a lack of shared responsibility, and where heritage isn’t cherished as a commons, collapse is more likely to lead to conflict and displacement. The competitive and degenerative tendency has been spreading across the Global South and in developing economies, so this is the most likely response wherever the Earth crisis hits.

Ruggedisation is a term used in the military for making tools robust in extreme circumstances. Alex Steffen is applying the term to places & complex systems to make them durable in context of collapsing eco-social systems (climate, biodiversity, health, food prices etc).

There’s very little attention to collapse and ruggedisation in our sector. Many environmental policies focus on how the organisation’s activities can continue while reducing harm, and, at best, on engaging their public with pro-environmental behaviours. These policies work more to save reputations than people, places and the planet.

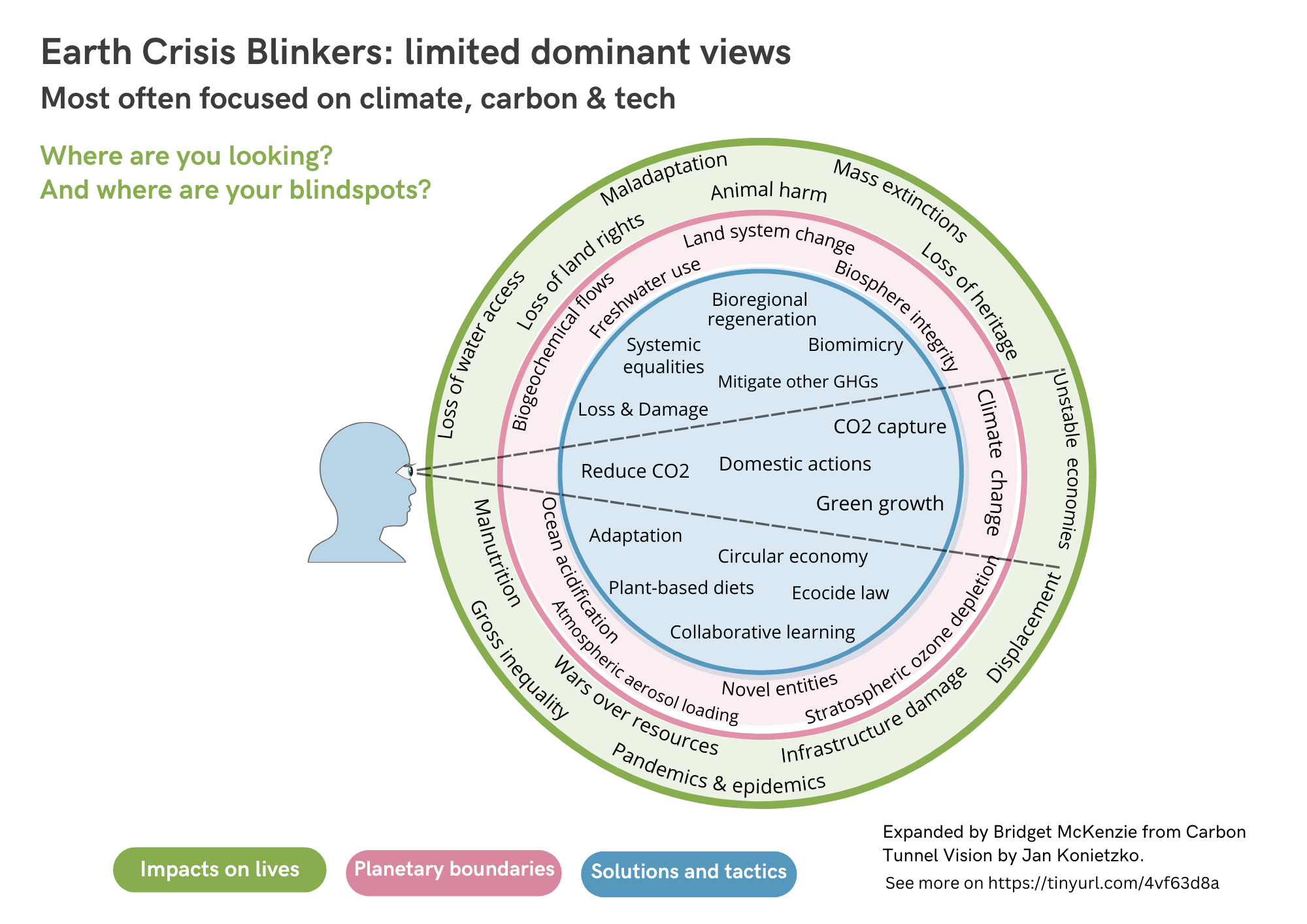

Management are not joining the dots, and are showing the same Earth Crisis Blinkers syndrome as the rest of society, which means only seeing carbon and climate mitigation, and not seeing the whole picture of breached planetary boundaries and potential solutions. This is ironic as our sector can contribute so much to public understanding of complex systems & histories of planetary change.

The Climate Heritage Network should be praised for their work-strand on Adaptation & Resilience. Their statement on this is about promoting the role of culture in adaptation plans, including indigenous knowledge.

This is vital. We also need to train and co-learn much more about how to protect heritage as impacts unfold. Heritage assets themselves need to be resilient and adaptable. Many are coastally-located, or are vulnerable to the knock-on impacts of social change when environments are fragile.

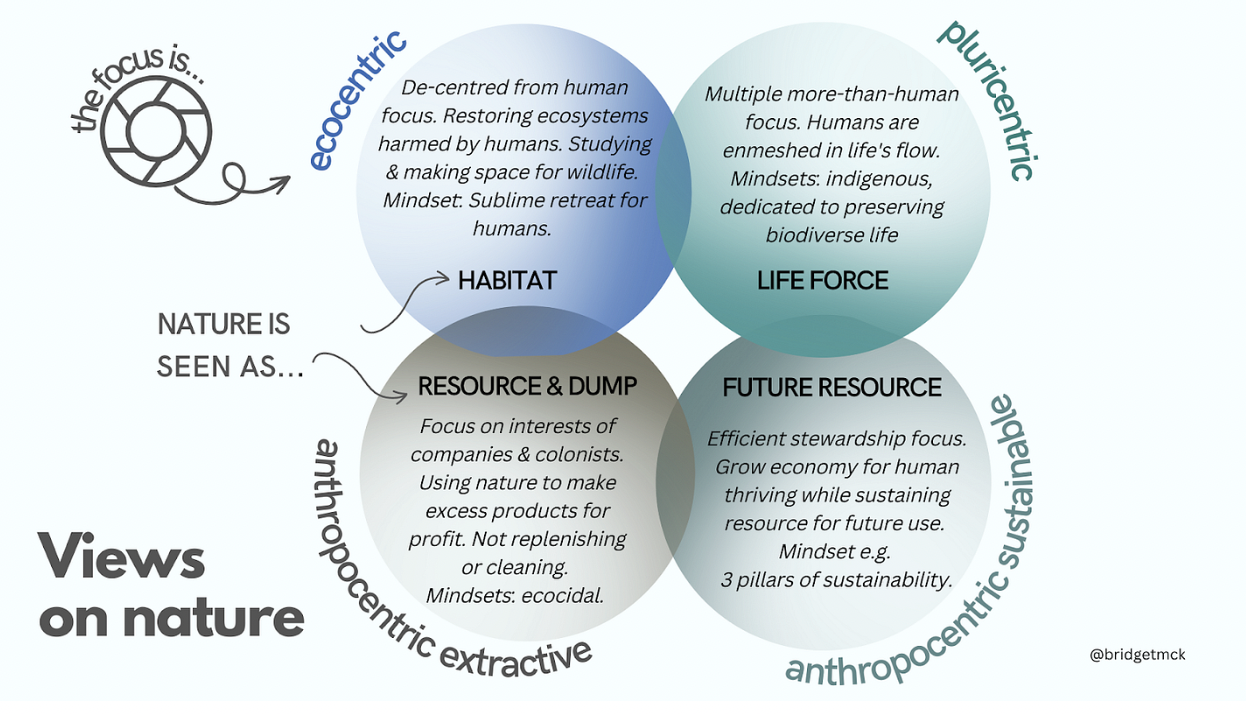

To explain ‘Regenerative Culture’, a regenerative approach in an organisation is indicated by dedicated missions and ambitious interventions that optimally contribute to regenerating social capacities, bioregional ecosystems and Earth’s operating systems.

One great advocate for designing regenerative culture is Daniel Christian Wahl. See, for example, and with an appropriate title, his piece ‘Sustainability is not enough: we need regenerative cultures’ And also see Joe Brewer who is living & teaching about this regenerative process.

My statement, that the time to be sustainable was 40 years ago is not to say that we’re too late to bother trying to live in sustainable ways. We get to choose our future, so we should honour that by choosing the pathway that helps continue civilised and biodiverse life, BUT we have to choose and act now in ways that are less palatable and clear than if we had acted 40 years ago. We’ve left it so late we have to radically adjust our mindsets and plans, beyond incrementalism, beyond wishful optimism.

Sustainability was about business continuity, reducing harm somewhat to minimise risks such as reputation damage, fines or litigation, or waste of resources. It was about a slow & steady transition assuming that climate impacts would kick in at some point later in the century. It was about bargaining with offsets to balance the good with the harm, and using PR to promote the good news stories and hiding the harm. Criticisms about this approach have been levelled much more at the business sector than the public cultural sector. Museums, arts and heritage can argue that we’re an antidote to consumerism, that we are inherently sustainable as we are not extractive or wasteful producers.

However, we can’t think like this anymore. We have to look at all the externalities and benefits of our activities. Are we contributing to flight-based tourism? Are we providing a social licence for extractive businesses, through our relationships with them? Why are we using concrete & steel for our new buildings? Are we actually protecting and using our assets for good in the longer term and in ecological ways, not just for people’s enjoyment?

Museums and heritage can aim to be transformative. Their mission could be to use their assets to activate people for individual, community and planetary regeneration and adaptation, not just to look after assets while trying to do a little good and protecting them as risks escalate.

This transformative work might include:

- running mutual aid schemes that use your spaces for warmth, healthy food growing, and community co-operation,

- being part of local provision of renewable energy,

- running scrap and upcycling schemes tied in with contemporary collecting projects,

- promoting regenerative agriculture, and using food in your retail that has been grown locally by such schemes

- retrofitting buildings, in ways that educate people how to do it themselves

- offering nature-connected education that prepares young people for the impacts of climate & biodiversity breakdown, or

- campaigning for streets that are car-free, and with ethical advertising, inviting visions of alternative adverts and street life.

These are multisolving actions that sustain heritage assets, and places & planet.

None of these kinds of actions by one organisation in one place will be enough in themselves to ruggedise places and stop harm. But, altogether, with other sectors & communities in our bioregions and internationally across our sector, we must do what we can.

See Holding Earth: Declaring Again for an alternative framework that starts to face the Earth crisis, read this for more on how museums are applying a more radical approach.