Lusto is the Finnish word for an annual ring of a tree, and it is the name for the Finnish Forest Museum. It’s a place to explore the Finnish forest as it grows over time, and the ways its use has changed over time. Now, Lusto is changing, to keep up with the times.

The most significant change in these times is due to the impacts of the global Earth crisis, offering a huge challenge to museums to represent it, to respond in resilient ways that protect heritage, and to activate their communities to mitigate and cope with its impacts. I was at Lusto as one of three independent mentors, rethinking how forest culture is re-interpreted as the museum is being renovated. The other mentors are Professor Dolly Jorgenson and Katriina Siivonen. Following some online meetings over the past two years, we finally met in situ with the staff team for tours and workshops, plus convivial evenings and mornings, including a Finnish sauna, a forest tour, and staying at the historic quirky Hotelli Punkaharju. These photos show the museum as it is, and a few hints of what is planned.

By 2024, Lusto will re-open with a different visitor flow, retail offer, facilities, narrative, interpretive philosophy and look-and-feel, and over the next couple of years fully evolve with rearranged collections, and a new national satellite as well as various digital contents. Artists and novelists are being commissioned to create new texts, games and environments to animate the spaces and effectively engage people. A key difference will be its re-arrangement by themes, each represented by a typical animal species. It will also have less content about forestry as an industry, softening and combining this with both more humanity and more ecology (more culture and more nature). The themes include Forest Nature, Forest Work, Green Gold (value / economy), Forest Folk, Lifeblood (well-being), and Valued Forest.

The idea is that it can be a Dynamic Museum, influential in society, and, for example, an agent for ecological reconstruction. This is an idea of a museum that creates breakthroughs and works with layers of time, anticipating and creating heritage futures. Leena Paaskoski, Katriina Siivonen and others have written on this here. See also this on Intangible Cultural Heritage will Revolutionise the Future.

The following are some thoughts that came to mind during the visit, about these questions:

- What are key mindsets for thinking about natural environments such as forests?

- What does it mean for a forest culture museum to be dynamic and activational in an Earth crisis?

- How do we generate a more engaging narrative flow amidst a combination of museum elements?

- What are some particular inspirations and ideas for Lusto or similar museums?

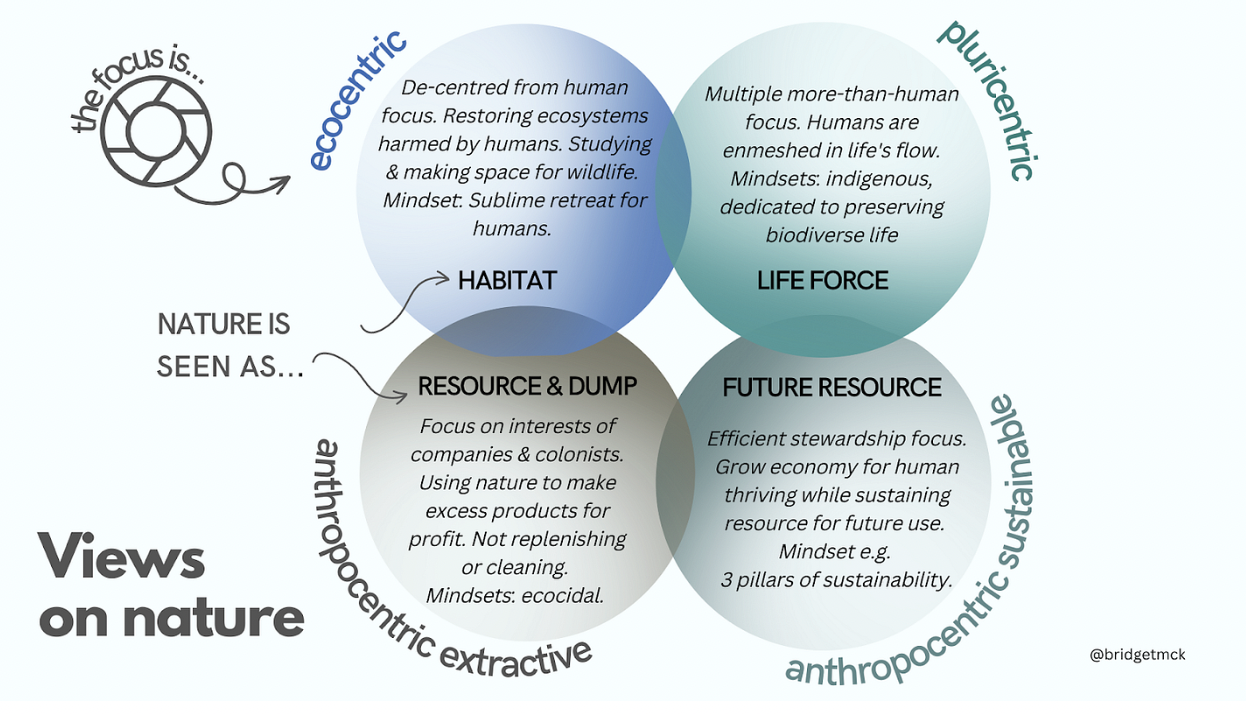

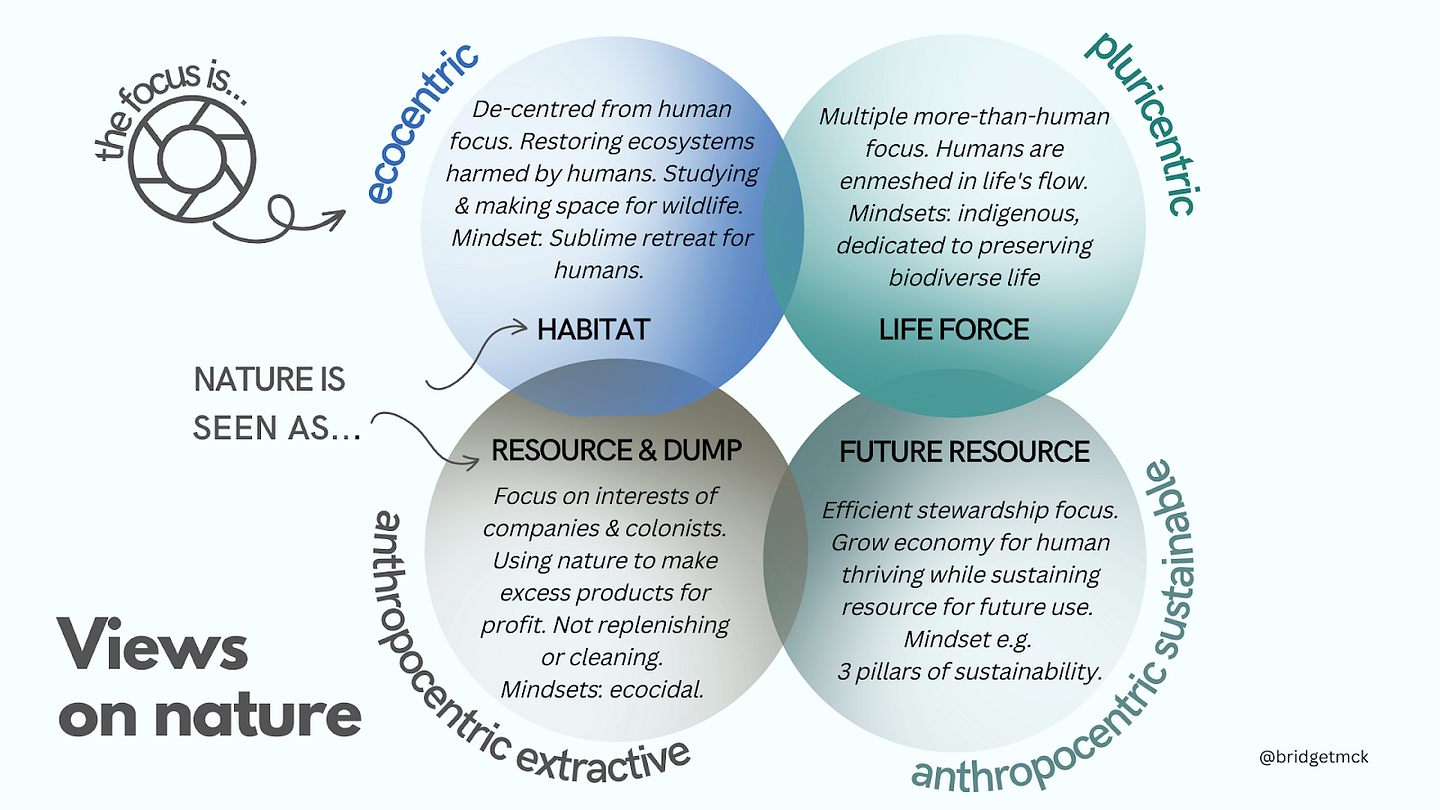

What are key mindsets for thinking about natural environments such as forests?

My diagram is informed by the IPBES report on multiple methods for assessing the value of nature. Anthropocentric extractivism has been the dominant mindset in the global north, and this has accelerated, but Finnish society has largely modelled a more sustainable and communal anthropocentric approach in its management of its forests (and lakes), with 60% of forest land owned by individual Finns. It also has ecocentric conservation movements and some protected habitats, as well as the fact that large areas of Finland are more wild and still habitat to species like bear, lynx and wolf.

Lusto is planning to reflect a range of different mindsets as reflected in Finnish history and culture, and to invite discussion on these values. My challenge is that to do justice to the Sámi peoples (and other indigenous and forest peoples), and to reflect the planetary emergency, there should be an overt expression of pluricentric mindsets. The museum plans to include a post-human space where Forest Nature dominates, that appears to be underground amidst root + mychorizzal systems and is symbolised by the Earthworm. However, one might question the term ‘post-human’. Even if humans stop harming it soon, the Earth will still take 10 million years to recover and to achieve a post-human state. Perhaps a more balanced term is the notion of the Symbiocene, to use Glenn Albrecht’s term for the coming era we need to create instead of the Anthropocene. In the Symbiocene, humans and more-than-human life are in symbiosis, living together, achieving the steady state that Earth systems require. This coming era can be prefigured partially in certain places that show climate-readiness, rewilding of ecosystems and degrowth of consumer capitalism. Finland as a nation is perhaps a better example than most. And so, Lusto might prefigure this way of being within its walls too, but to do so it must:

- acknowledge the problem of global ecological collapse — such as the near tipping-point state of the Amazon forest — and

- make an overt ethical commitment to preserving integrity of the whole biosphere, not just in Finland e.g. by including The Earth Charter.

Being pluricentric doesn’t mean enabling the several views to be heard that are dominant in one context, but expanding to include perspectives that can’t be voiced, that have been suppressed or lost, or from other cultures and countries, or that might be queer in various ways. Even if the focus of the discussion is on one ecosystem or nation, these other perspectives will enrich understanding within that context.

What does it mean for a forest culture museum to be dynamic and activational in an Earth crisis?

The rapid onset of the Earth crisis beyond predictions challenges the notion of continuity that underpins the founding rationales of museums. Everything has changed. Planet Earth is becoming a museum in itself, displaying the traces of systems, cultures and species coming to an end. Museums can and should hold a mirror to this global museum of ‘endlings’, highlighting harmful systems as human-constructed rather than as an inevitable feature of progress.

A dynamic museum needs to respond to these big changes, which means seeking a bigger network through which to have influence, and being more direct about the influence it wants to have. How can museums:

- Reflect these planetary-scale changes within their walls?

- Overcome political resistance from their funders and boards to what might seem radical thinking?

- And create satisfying and accessible narratives for audiences?

Perhaps they can achieve all these by demonstrating particular positive impacts on the environment, as well as the local and global economy and society. They can use collections to stimulate safe but powerful conversations, to inspire the imagining of alternative futures, and support people to take action that prefigures the system changes needed in the world.

Any museum can be biomimetic, but a forest culture museum even more so. It can be more forest.

- Forests are the biochemical opposite of fossil-fuelled human settlements in that they emit oxygen and salutogenic substances into the air and absorb CO2 and pollutants. Can Lusto be more like this?

- Forests are communities of care, via root and fungi systems, nursing, defending and feeding each other, particularly the young, sick and dying. Can Lusto be more like this?

- Forest stabilises and fertilises land against soil erosion, flood, drought and other impacts of climate breakdown and agricultural ecocide. Can Lusto be more like this?

How do we generate a more engaging narrative flow amidst a combination of museum elements?

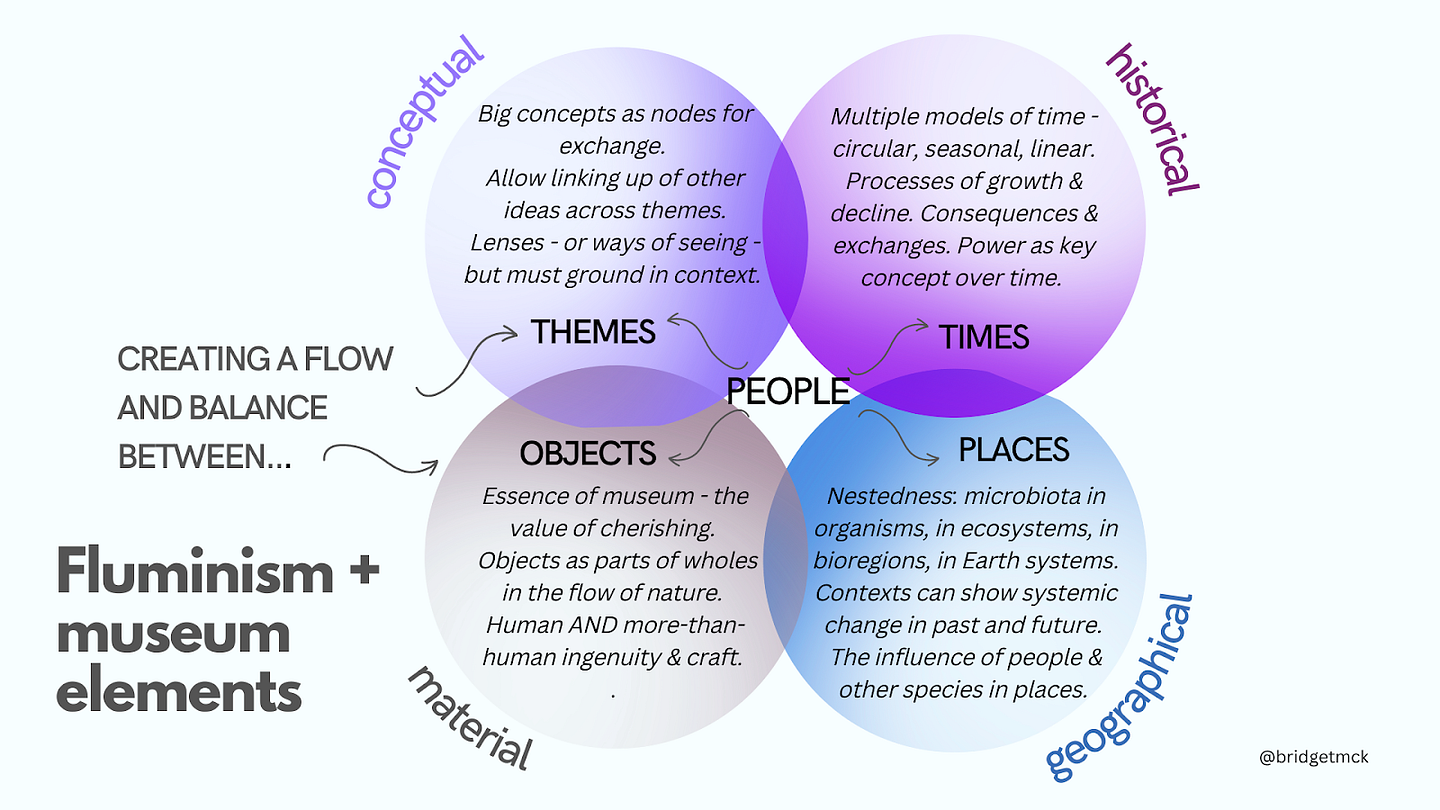

Attaining a flow between the elements, creating a forest-like narrative that offers choice of routes but also coherence and meaning, means being more informed by relational ecological principles. A key idea here to hold onto is fluminism. This is an eco-philosophy from Ginny Battson, who says: “Following Lynn Margulis’s trajectory of symbiotic thought, I see all interconnections or unions as a dynamic force of intelligence with which all porous life engages in flows to varying degrees,” and “Even random acts of supposed subconscious union […] are then more consciously repeated when the unions…lead towards life flourishing.” This dynamic flourishing doesn’t just describe the biophilic qualities of life on Earth, as if they can just be left alone without us. Fluminism is a philosophy for human activism to inform the design or choices to help life to flourish, given that it is so damaged by our actions now.

So, how can this approach work through the elements of a museum, particularly for Lusto?

Themes:

- Themes are big ideas that serve as nodes for exchange or linking other key concepts or events.

- Lusto might highlight some other concepts crossing through all the themes e.g. Animal Labour, Extraction, Safety, Community, Biochemical exchange, Climate, Resilience, the Wild, Indigeneity, Foraging…

- Themes are lenses for seeing across times, places, objects and people, but they can be too abstract. They can mystify as much as they can illuminate if they’re not grounded in context, by using maps, local voices, images of the place changing over time, and so on….[which links to…]

Places:

- The nestedness of places should be shown. For example, showing microbiota in organisms, which are in ecosystems, within bioregions, that are nested in Earth systems.

- This nestedness can be overlaid with cultural and political ways of visualising relationships in places, showing the influence of peoples and other species in places.

- Geographical contexts can show systemic and large-scale change in the deep and recent past, and evidenced future scenarios…[which links to…]

Times:

- Exploring multiple models of time — circular, seasonal, linear (reflecting indigenous views)

- Historical periods — continuity and discontinuity reflected in human and natural places over time.

- Exploring slow (e.g. ancient trees, a whole forest community over time, sustainable wood products) and fast (e.g. efficient labour and transport, when & where there is fast tree growth).

- Processes of growth and decline not as a story of inevitable human progress but as a series of consequences and exchanges.

- Dynamism as a key concept over time, which can be shown well with objects…[which links to…]

Objects:

- Objects are the essence of museums — representing the value of cherishing material culture and evidence.

- BUT, objects should be seen as parts of ‘wholes’ in the mesh of nature.

- Iconic objects might be used for spectacle but also as lenses for understanding interconnectedness and other concepts.

- Objects and specimens can highlight human AND more-than-human ingenuity and craft….[which links to…]

People:

- As humans, we identify somewhat with all other humans. Another person’s story doesn’t have to be identical with our own to resonate with us.

- Museums can humanise narrative experiences with the struggle, power, pain, and passion of named or pictured people, whether famous or unknown.

- We can also represent non-human beings (including rivers and forests) as ‘people’ — as sacred beings deserving of rights.

What are some particular inspirations and ideas for Lusto or similar museums?

An activational museum achieves impact through a range of means:

- The visitor experience — whether it is occasional or frequent, long or short, free-choice or guided, dipping in or seeing the whole

- Events, community projects and outreach courses that might take place within or outside the museum

- Multimedia content and collections discovered online

- Press and social media that responds to issues and events in a timely way, in relevant channels

- Retail products and publications available in the museum, or from an online shop or from franchises

- Relationships between staff and stakeholders in the museum profession, in relevant industries, in academia, campaigns or community groups.

- Art and research commissions and residencies.

I specify all of these because across the museum sector so much resource and time is spent in crafting the visible visitor experience and less attention is given to the interactions between people and ideas that might happen outside of the traditional visit experience, but which still might have a great deal of impact.

All that said, it is possible and exciting to create a visitor experience that is artful, playful, conversational and emotionally impactful. On my way back from Finland via Amsterdam, on the recommendation of Colin Sterling I went to the new ARTIS Groote Museum. You can see my photos of the museum installations here. Through beautifully created and curated artefacts, interactives, poetic texts and art commissions they allow the visitor to explore big ideas about nature and humanity. Many of the exhibits are about trees, forests, soil and woodland animals, and could be a great inspiration for Lusto’s team.

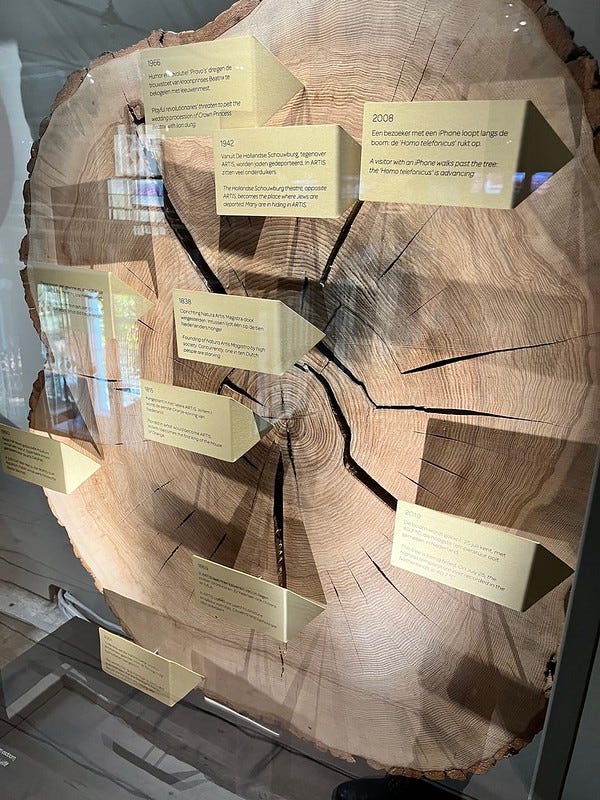

For example, a timeline doesn’t have to be linear, but could use ‘lustos’, or annual rings.

Some other ideas and inspirations that came to me include:

- Giving visitors a ‘key’, a handling object such as wooden treen that they could carry round to find resonances throughout the display. (This could be digital too, to collect experiences and ideas as with experiments of museums like the Cooper Hewitt).

- The museum experience could conclude with something like a Wish Tree — where visitors might take away ideas for Acts of Tree Kindness while leaving behind a pledge to the planet or gift to the museum.

- Conversations inspired by artworks like the Parliament of Trees, by Elmo Virmijs, in Amsterdam in October 2022.

- Using visual ideas from ways that knowledge has been represented by tree forms e.g. see The Book of Trees — on visualising knowledge — by Daniel Lima.

- Human stories of how forest workers have cared for each other to keep safe and avoid accidents.

- Reproductions of artworks that show the romanticism of the forest, and exploring how the idea of forest is constructed through representation.

It was a real pleasure taking part in this workshop, and the beauty of this part of Finland is definitely under my skin. I can imagine that the renovated Lusto will be effective and beautiful, inspiring its visitors to feel connected to the forest, to think about its histories and care about its future.