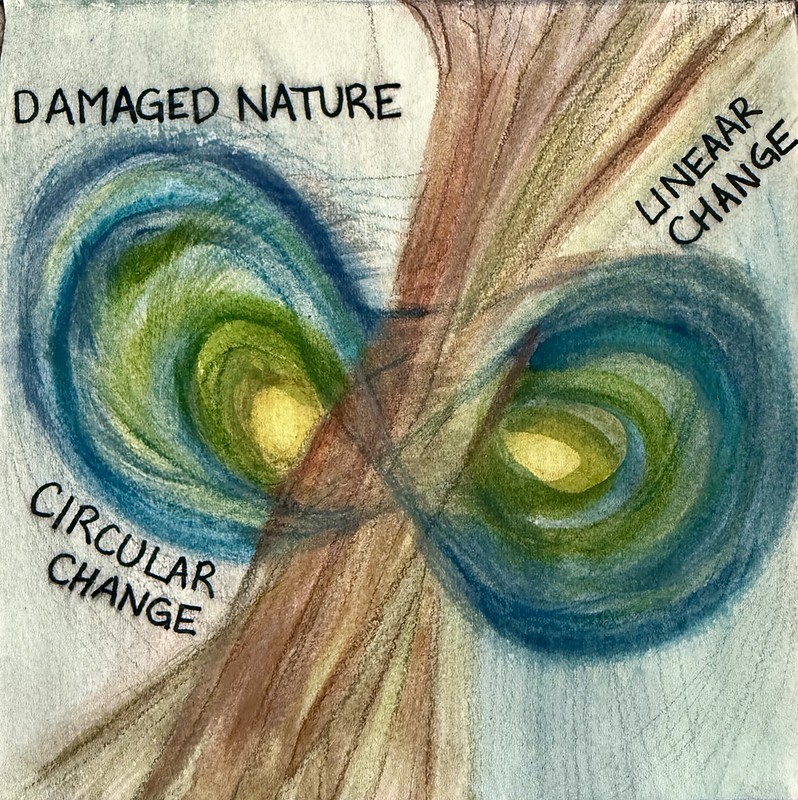

Links in time and space, between Nazi propaganda, underwater photography and coral reef bleaching, as a way to understand representation, complicity in and denial of great harms.

Imagine a drone camera hovering over Mar-a-Lago, with special powers to see into rooms, beneath layers and into past events. Maybe it can look inside a big locked room, with thousands of (white) papers about Trump’s 2020 violent coup of the White House.

I imagine you might see a lot of deferential (white) people scurrying around, perhaps busily redacting truths, or bleaching after unpleasant liquid spills. You might detect the pale ghosts of past visitors who have been sexually and emotionally abused. You might see inside vast bins of detritus, plaster and wallpaper from endless rebuilding and gilding of rooms, bags of medical waste and less-than-white nappies. And on the land around, where years before there might have been diverse grasses, birds and reptiles, you now might find patches of pale sand and accretions of white golf balls.

After scanning this scene of white artifice and hidden dirt, you might zoom over to the University of Miami’s Coral Reef Futures Lab.

That is, if it still exists, if it hasn’t already been so etiolated by Trump’s cuts to environmental science that there is no life left but some unoccupied edifices. In 2023, its marine scientists recorded water temperatures in Manatee Bay, Key Largo, of 38.4 degrees Celsius, the hottest ever recorded. But it’s not the only reef site experiencing a thermogeddon (a heat event that kills off significant biotic mass, leading to functional extinctions of key species). Add to this the effect of ocean acidification, chemical and plastic pollution and bottom trawling.

Vividness of colour and of interspecies relationships is drained, like in those before-and-after photos of Gaza, the slide across from colourful roofs and parks to a powdery mush of grey concrete. Bleaching is now seen in 84 per cent of coral reefs in at least 83 territories. And it is an ongoing process of heat death.

The priority measures to protect coral reefs include stopping Global Heating from rapidly worsening, and reducing pollution from agriculture, plastics, shipping and oil drilling. Conservation actions include regenerating marine ecosystems by controlling overfishing, planting seaweeds, and relocating key species to places where cooler temperatures allow habitats to thrive. In addition, scientists are studying which corals and marine animals are most resilient to thermal stress, so that they can be selectively bred and reintroduced.

There are too many obstacles to these measures. International laws are unsuited to the most international matter of all — the environment. Experimental science to help ecosystem adaptation struggles to get permits. The long-standing campaign to introduce Ecocide as the Fifth International Crime Against Peace does not yet have enough political traction. Agreements to mitigate global heating are still voluntary and far too slow. The ‘Fossil Fascists’ or ‘Pollutocrats’ hold power by owning the media, funding and lobbying politicians to delay action, for extractive licences and land-grabs.

Now, ready yourself for a couple of leaps, in place and time. We are making a map of connections. Let’s go back in time to the 1930s and 1940s, with developments in underwater and colour photography and explorations of flourishing oceanic ecosystems. Films started to find their way into cinemas.

Steve Jones, in his book ‘Coral: A Pessimist in Paradise’, describes an early underwater documentary about the Great Barrier Reef, noting that the British censors cut out scenes of turtles laying eggs, on the grounds of indecency. This was an attempt to deny the facts of the generation of life, which makes this living planet so exquisitely precious.

Jacques Cousteau invented the aqualung in 1942, and in 1956, he released the film The Silent World, becoming a televisual celebrity. This film was in full techni-colour and viewers were utterly entranced by this strange paradise. While coal emissions, wars, whaling and excessive fishing had already begun harming ocean life, coral reefs were still vivid at this time.

Of course, this mid-century era is associated in our minds less with oceanic imagery and more with the rise of fascism and the Second World War.

At this time, people were thirsty for entertainment in contrast to the horrors and strains of life. They were vulnerable to believing what they were seeing, such was the magic of the big screen. Cinemas showed news and propaganda reels to their populations about scientific progress and national successes. In Germany (and later in Occupied Territories), audiences would have seen Leni Riefenstahl’s propaganda films, which she made for Hitler, such as The Triumph of the Will (1935). This documents vast crowds of citizens and armed forces flocking to hail the Führer. The opening scenes are of aerial footage over cities, the distance rendering the buildings and crowds like intricate reefs. The plane descends, and Hitler appears like a god from a sky-chariot. People respond with salutes and chants in unison. Whether the crowd’s motivations are from fearful command, social contagion or genuine conviction, the film represents entire urban populations supporting his capture of power. These images reinforce their own truth and reproduce it as reality.

The opening scenes of the sprawling reef-like city remind me of similar aerial footage taken by Allied Forces towards the end of the War, over devastated cities. The Allies showed a film of Dresden — intensely bombed, with 25,000 civilians killed in one attack in February 1945 — to show that they had made a strategic attack, but also to counter German propaganda and to shock the public into supporting surrender. However, it also triggered moral debates amongst the Allies about terror bombing, which was later intensified by the Allies dropping nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

War is never black and white.

Moral debates about mass destruction and the knowing will to power preoccupied governments, academics, writers and many citizens in the 1940s and 1950s. Leni Riefenstahl was questioned on how much she knew about and supported Hitler’s intentions. She insisted she knew nothing of his genocidal plans, and later apologised for her role. She claimed the films were documentary and aesthetic constructions, that she was interested only in recording significant events, and in the camera techniques that capture their beauty, and that she had no concern for the ideology behind them.

When humans have become like gods, such that their technology can surveil and burn entire cities and landscapes and poison them for generations, can our global civilisation sustain the separation of nations? Is internationalism the only route to peace? While internationalism makes strong practical and moral sense, and many hopeful institutions, conferences and treaties have been made, the ‘realpolitik’ of extractive capitalism has grown like a cancer. There is just too much world, too much real estate, for these bad actors not to want to capture and exploit as much as possible in a global race for profit.

Vast expanses of ocean were used in the 1950s and 60s as test grounds for nuclear weapons, disregarding the multitudes of species, habitats and human settlements that would be wiped out or displaced. Large areas of the Great Barrier Reef have been sacrificed to developments supporting Australia’s fossil fuel and shipping industries. The meat and logging industries have turned our planet’s forest paradises — and the lungs for our stable climate — into deserts for livestock grazing and crop plantations. Trump says he wants Greenland as a nice piece of real estate, and probably for his techno-utopian mates to build free cities, as well as to cement the Russia-USA agreements for carving up the world.

In 2024, scientists reported that the planet’s carbon sinks were no longer absorbing as much CO2 as humans were emitting. Did you know that? Did you hear about this? The news was erased, a white-out.

Leni Riefenstahl is famous for her films for Hitler, but decades of her life were dedicated to underwater filming of reefs. She used the most advanced technicolour cameras, choosing to swap lenses for different motifs, and her favourite motif was ‘still lifes’. There is an implicit distance in her aesthetic eye, hungrily looking for motifs and drawn to colours. She doesn’t describe sensate beings who are communicating and weaving relationships.

She did express environmental concern: “when you have experienced this vitality of the sea, you can only hope with all your heart that it will be preserved for all of us and for generations. The submarine world has grown so slowly, but now materialism, brutality and carelessness can destroy or seriously threaten to destroy it in less than one generation.” (Visions of Paradise, 1978)

Riefenstahl was still alive when the first mass bleaching events occurred due to global heating (in the late 1990s and 2002). I’m not sure if she witnessed this, although she did continue diving until 2000, and she died at 101 in 2002. I am sure her concern for ocean life was genuine. She said she was following in Jacques Cousteau’s footsteps of raising public interest in the ‘blue planet’.

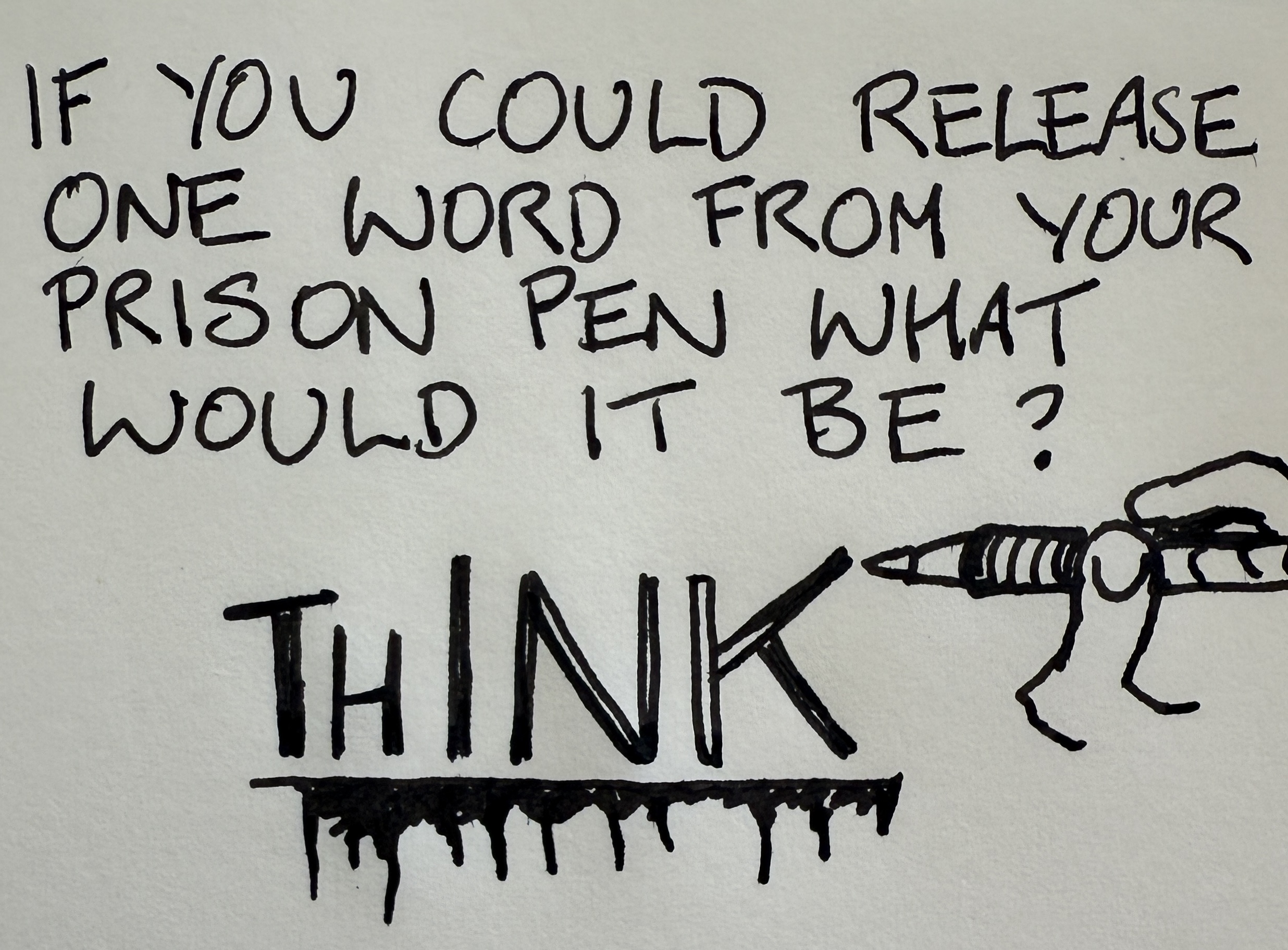

However, her work raises questions, not directed at her, but for all of us who are involved in acts of representation, about the ethics of a dispassionate gaze. Here are a few questions that come to mind:

Where should we direct our cameras?

When do we put down our cameras to help in other ways?

What other methods, or lenses, can we use to scrutinise and expose?

When our friends and colleagues find themselves entangled in complicity with bad actors, harm-deniers and gas-lighters, how do we help them out of it?

How do we practice for the intensification of this harm-denial?

How can art and storytelling help us practice?

PS This contains my original artwork and writing. I posted a reel of this piece on Meta, which said that users are free to do what they want with my content. Obviously, please don’t take my work and claim it as your own or use it in AI pieces. This automation of content-creation is a huge part of the problem that I’m addressing in the piece, albeit without naming it above. I’m aware of my complicity in belonging to and using Meta platforms.