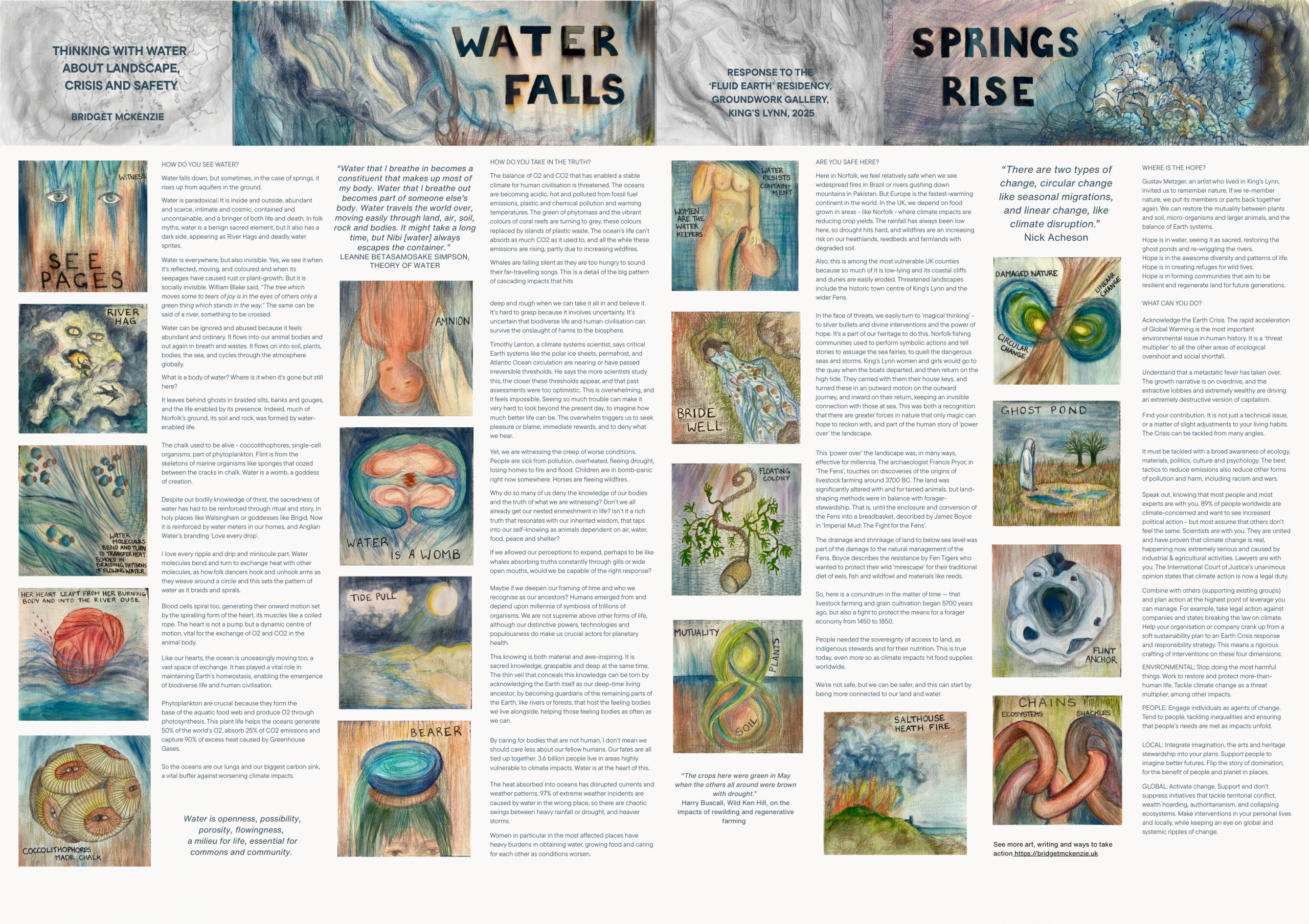

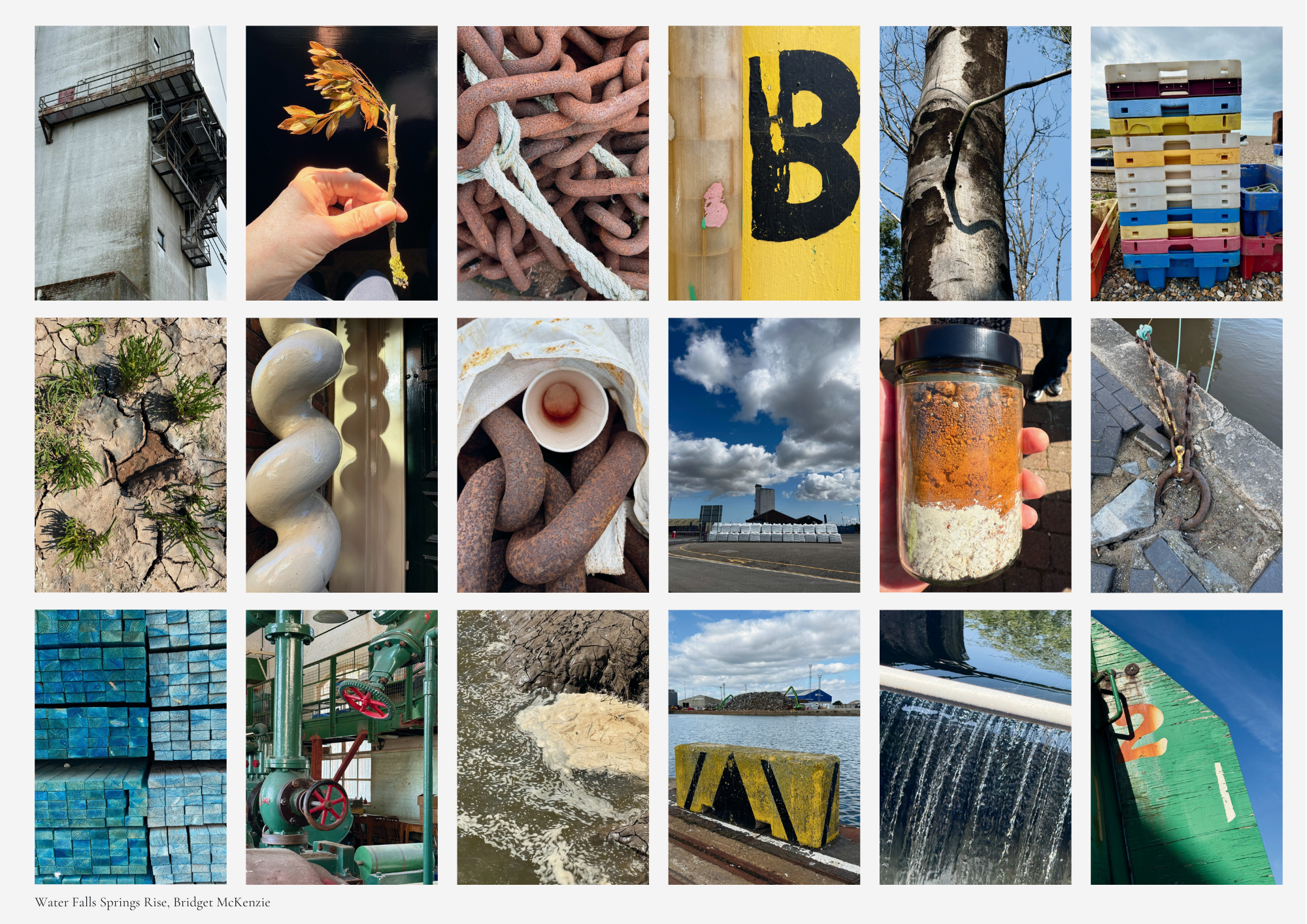

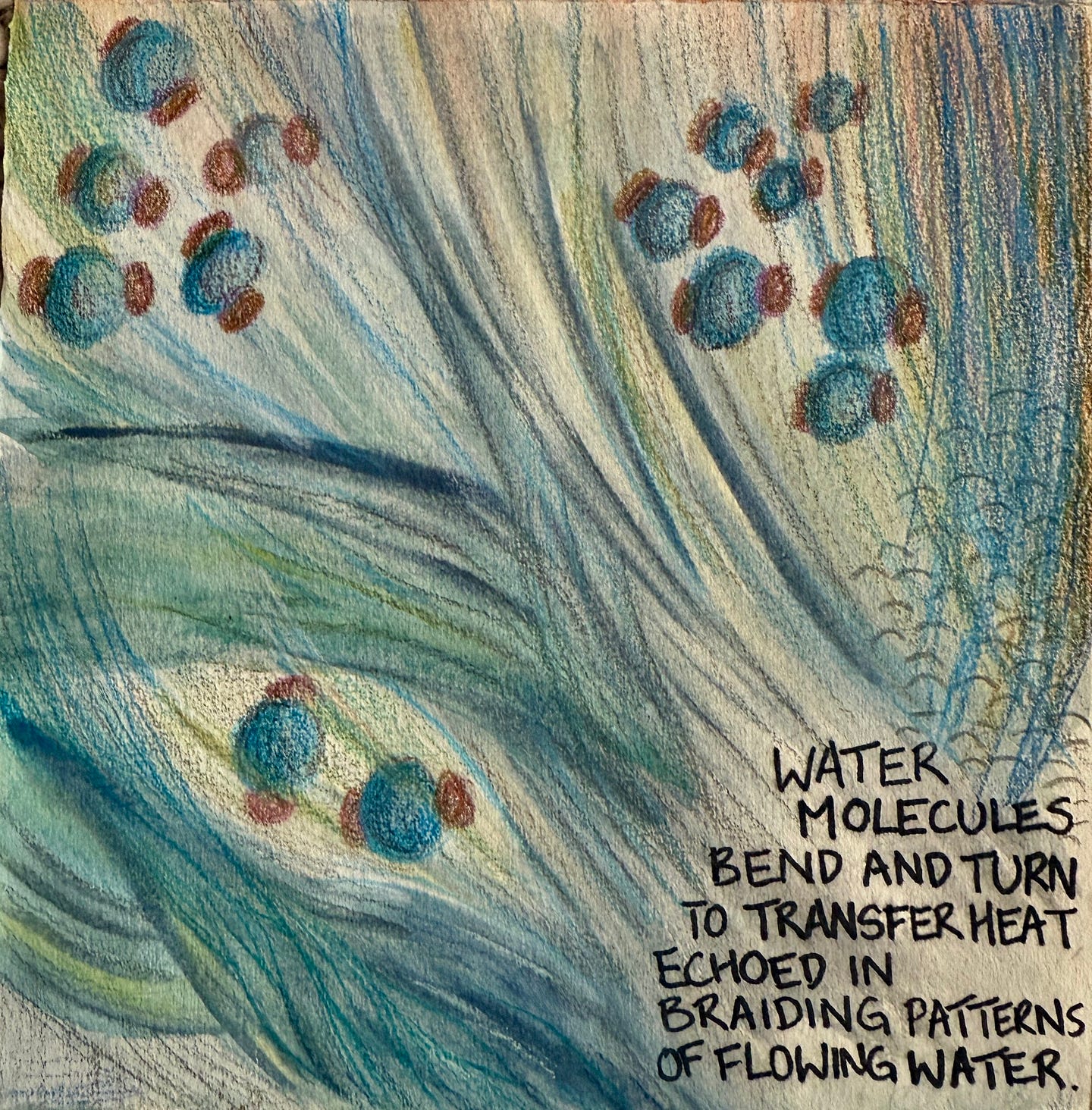

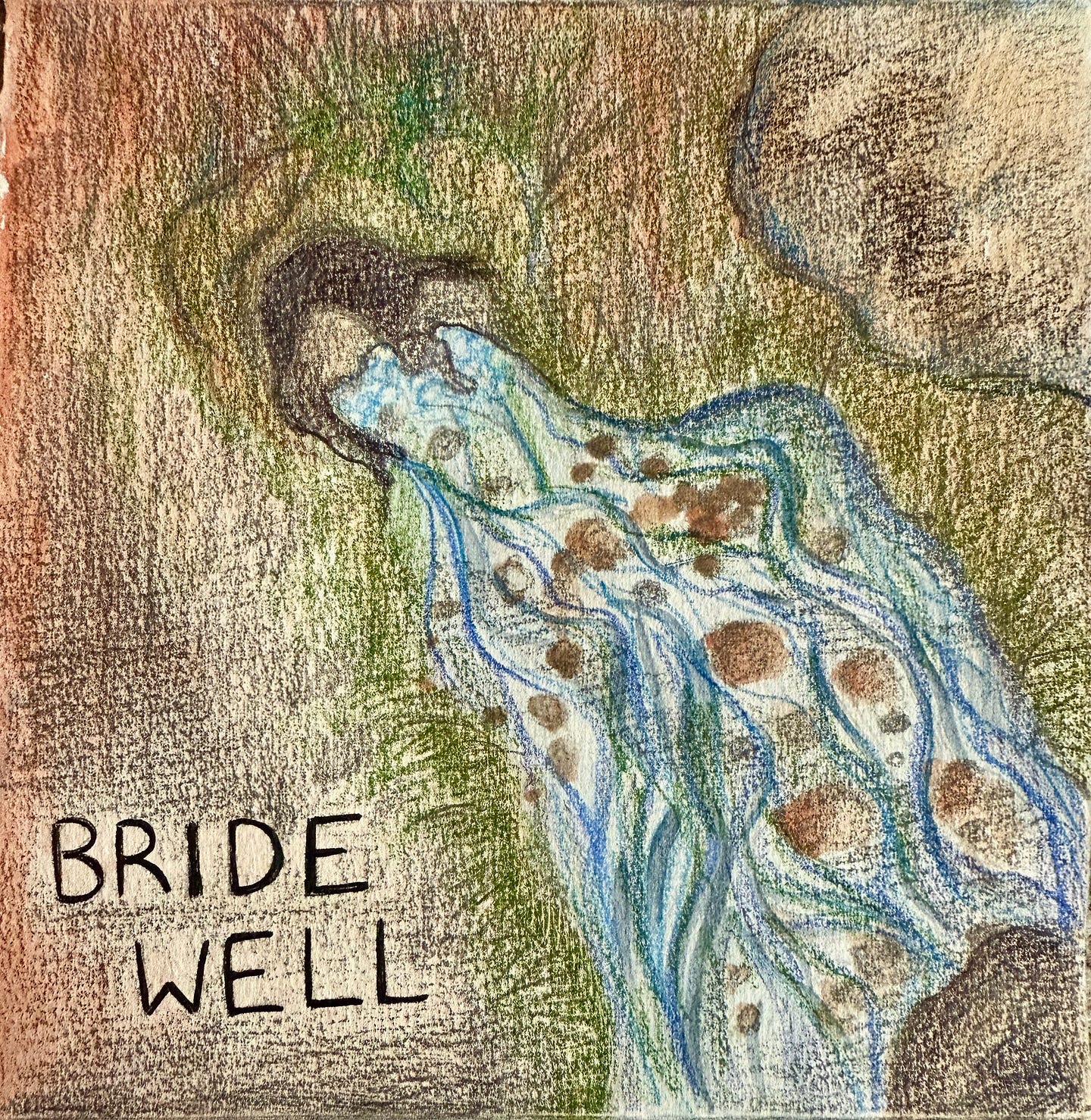

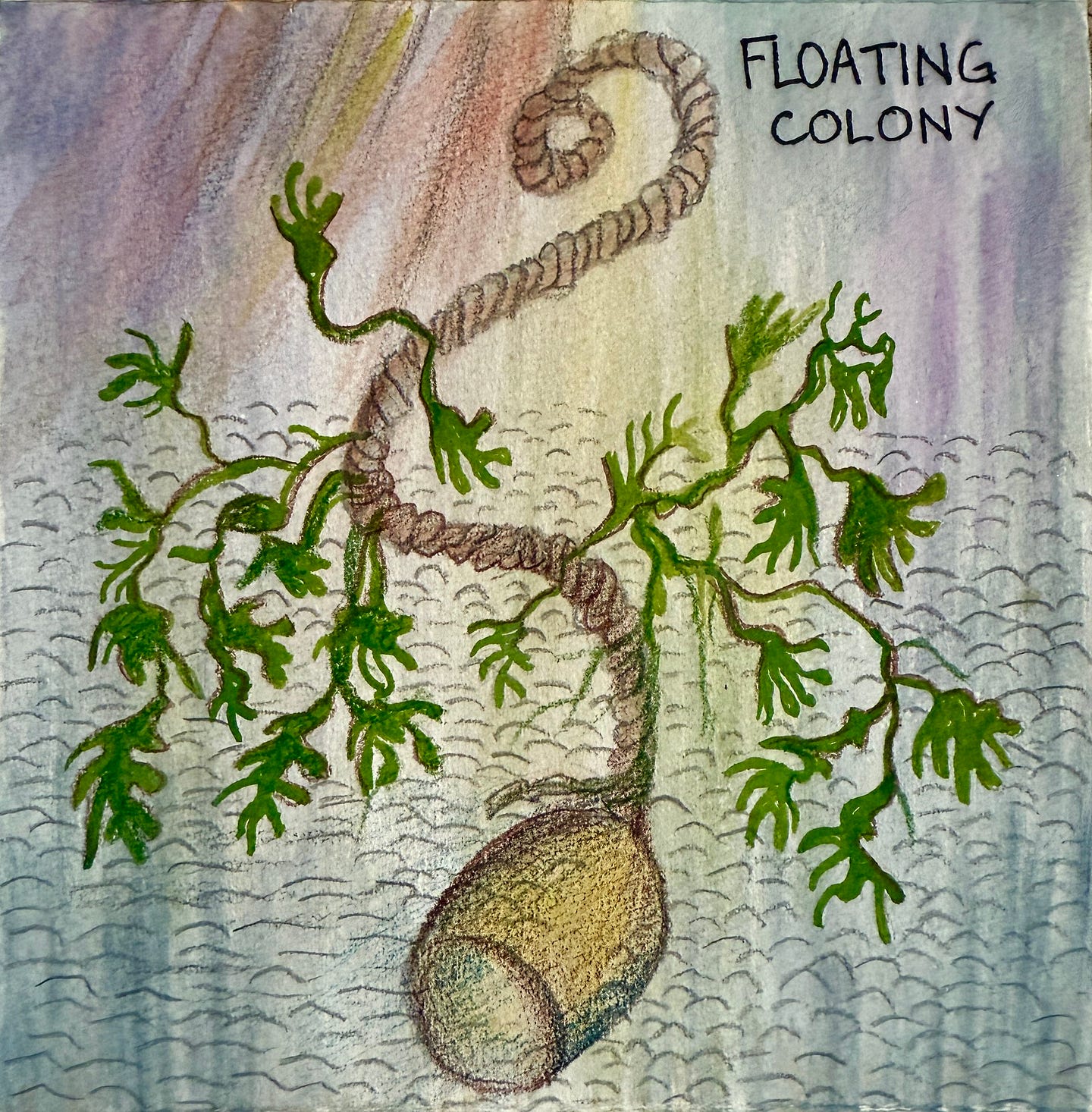

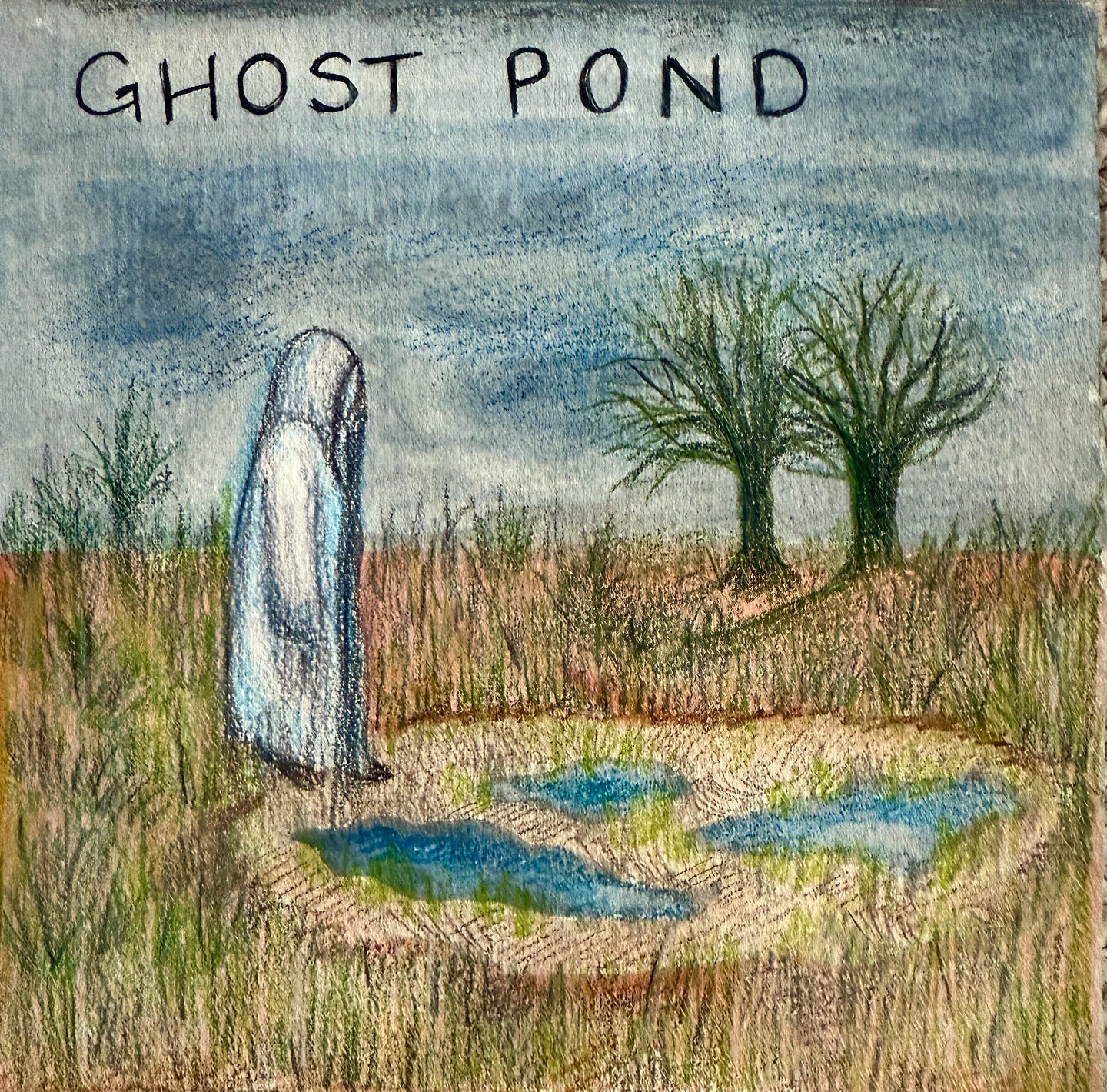

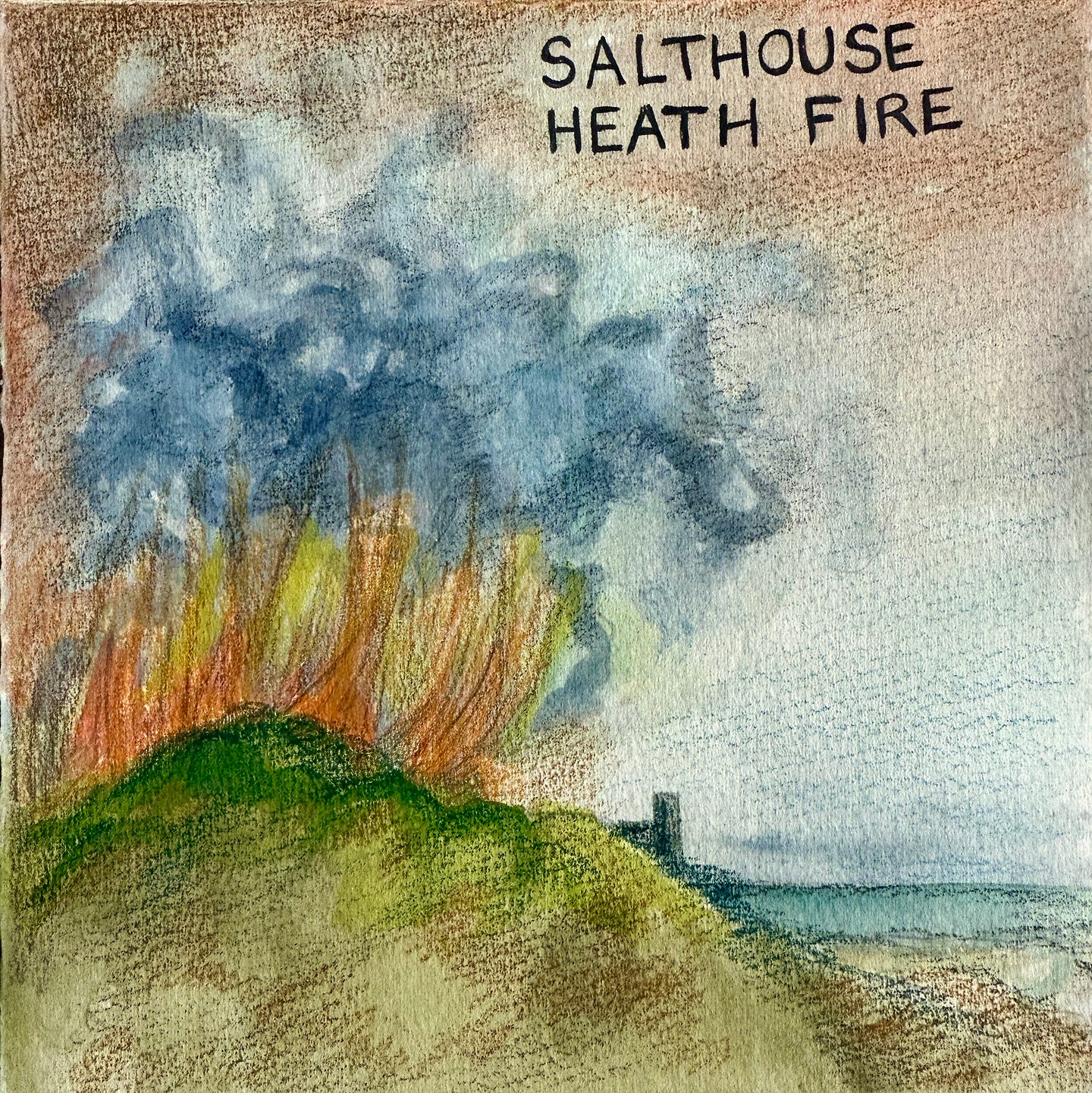

This is the text and illustrations from a sculptural book that I have made as one outcome of my participation in the Fluid Earth residency at Groundwork Gallery, King’s Lynn. My other book piece was Wild Nature Human Nature, which you will also be able to see in the exhibition. I am displaying the eighteen square illustrations in two hanging pieces. The exhibition opens on 4th October.

Get in touch at bridget.mckenzie@flowassociates.com if you would like to buy a printable or printed version of the book. This image is a low-res version of a different layout to give you a sense of it.

THINKING WITH WATER ABOUT LANDSCAPE, CRISIS AND SAFETY

HOW DO YOU SEE WATER?

Water falls down, but sometimes, in the case of springs, it rises up from aquifers in the ground.

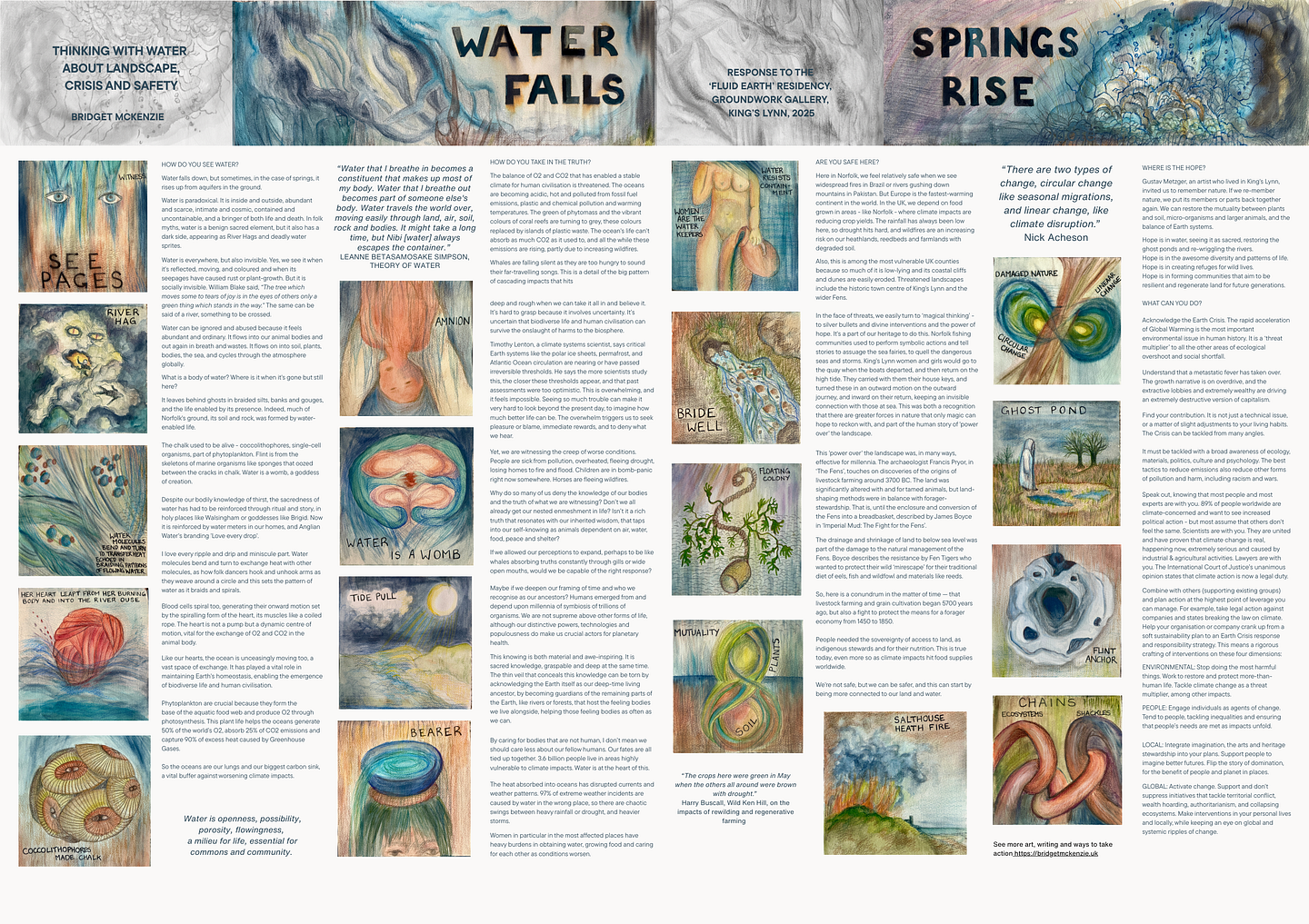

Water is paradoxical. It is inside and outside, abundant and scarce, intimate and cosmic, contained and uncontainable, and a bringer of both life and death. In folk myths, water is a benign sacred element, but it also has a dark side, appearing as River Hags and deadly water sprites.

Water is everywhere, but also invisible. Yes, we see it when it’s reflected, moving, and coloured and when its seepages have caused rust or plant-growth. But it is socially invisible. William Blake said, “The tree which moves some to tears of joy is in the eyes of others only a green thing which stands in the way.” The same can be said of a river, something to be crossed.

Water can be ignored and abused because it feels abundant and ordinary. It flows into our animal bodies and out again in breath and wastes. It flows on into soil, plants, bodies, the sea, and cycles through the atmosphere globally.

What is a body of water? Where is it when it’s gone but still here?

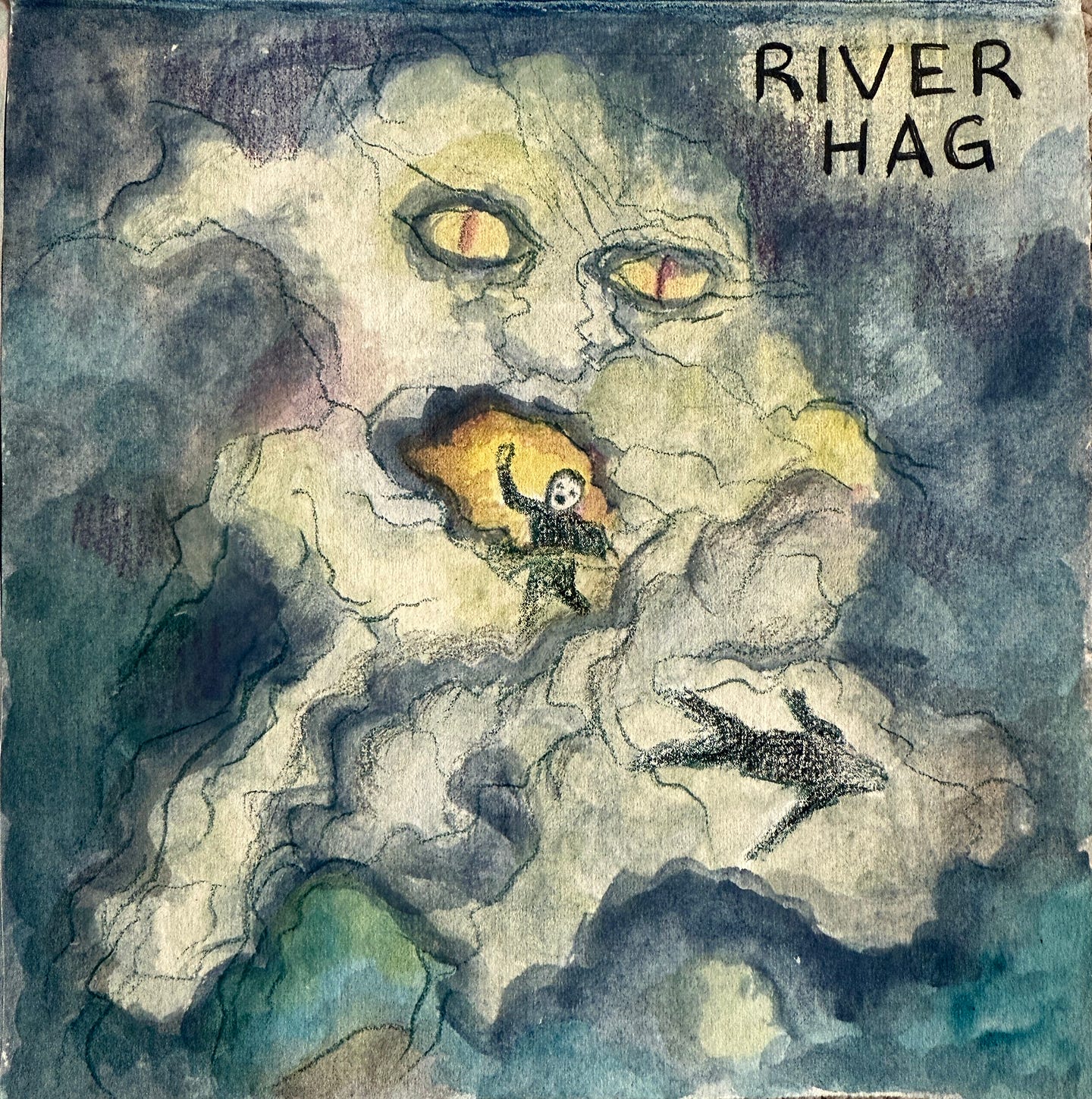

It leaves behind ghosts in braided silts, banks and gouges, and the life enabled by its presence. Indeed, much of Norfolk’s ground, its soil and rock, was formed by water-enabled life.

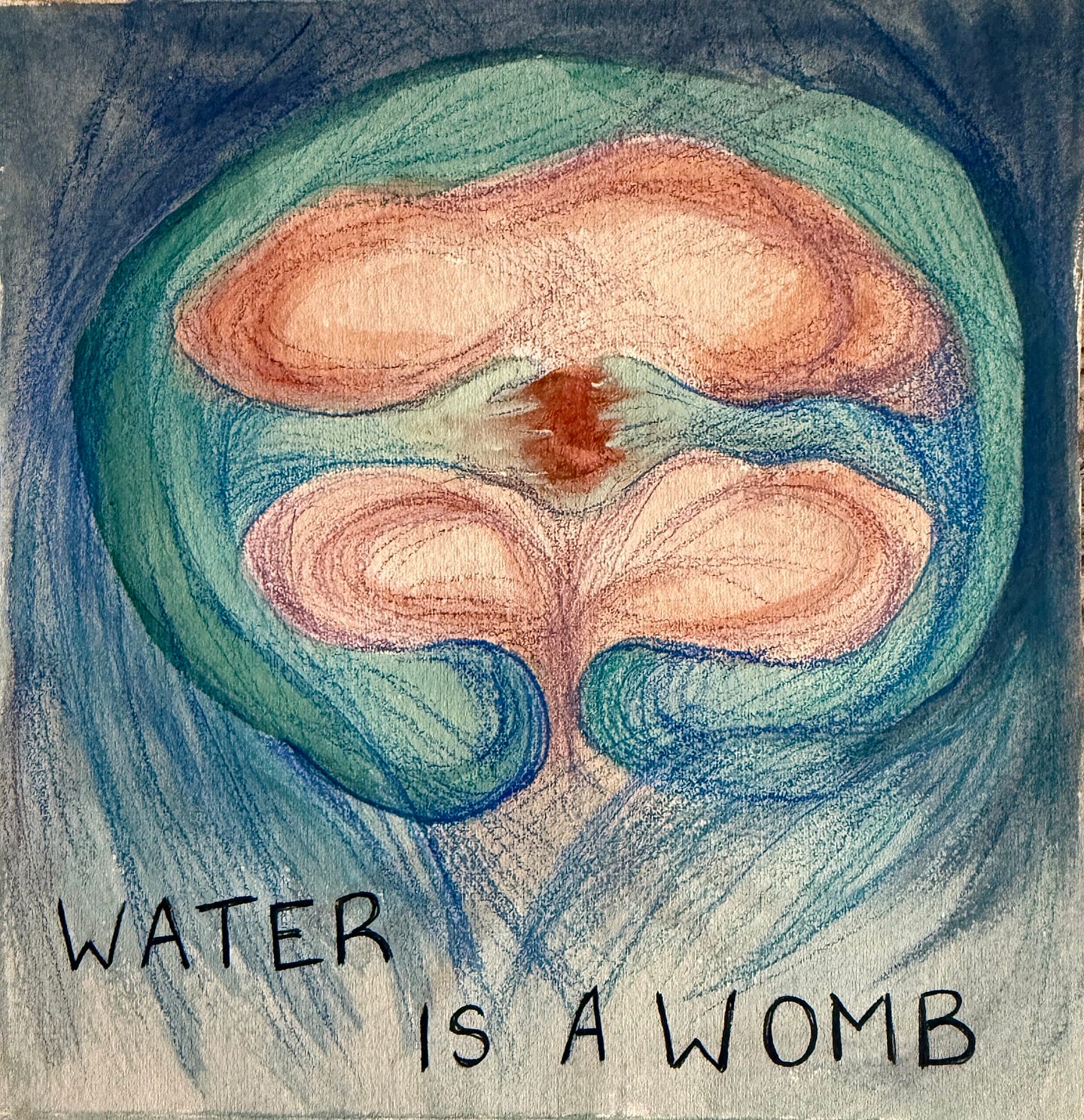

The chalk used to be alive — coccolithophores, single-cell organisms, part of phytoplankton. Flint is from the skeletons of marine organisms like sponges that oozed between the cracks in chalk. Water is a womb, a goddess of creation.

Despite our bodily knowledge of thirst, the sacredness of water has had to be reinforced through ritual and story, in holy places like Walsingham or goddesses like Brigid. Now it is reinforced by water meters in our homes, and Anglian Water’s branding ‘Love every drop’.

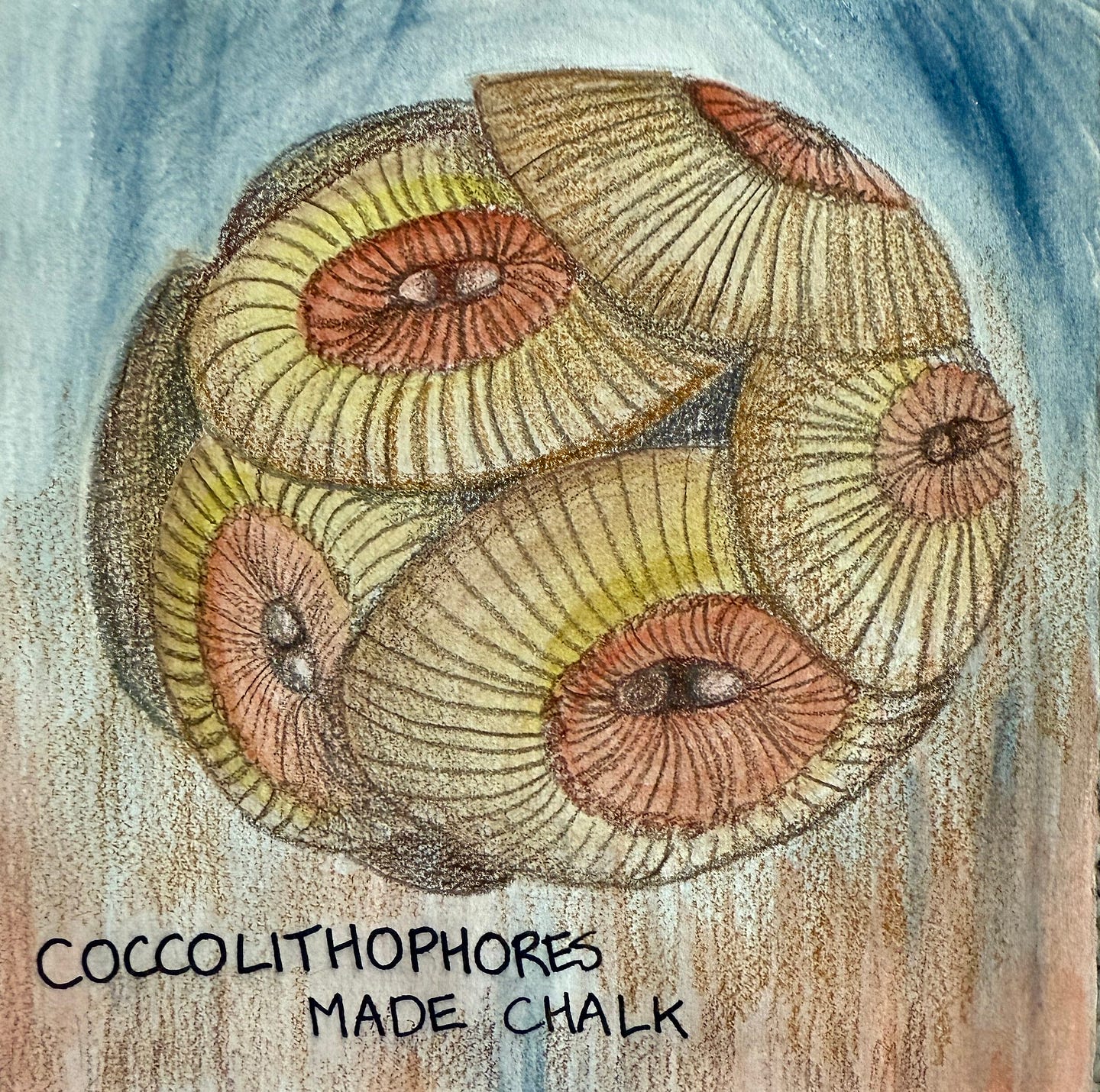

I love every ripple and drip and miniscule part. Water molecules bend and turn to exchange heat with other molecules, as how folk dancers hook and unhook arms as they weave around a circle and this sets the pattern of water as it braids and spirals.

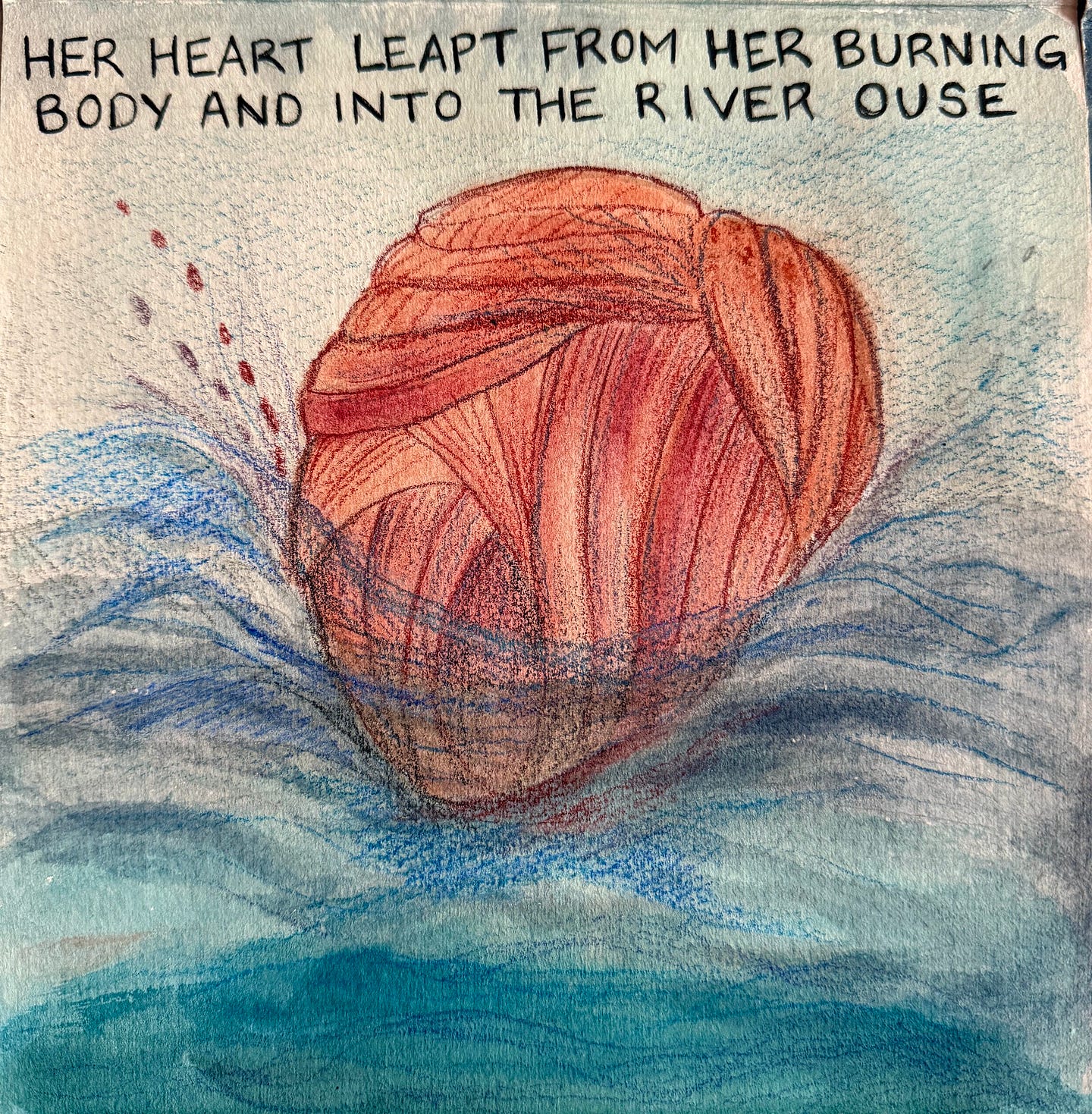

Blood cells spiral too, generating their onward motion set by the spiralling form of the heart, its muscles like a coiled rope. The heart is not a pump but a dynamic centre of motion, vital for the exchange of O2 and CO2 in the animal body.

Like our hearts, the ocean is unceasingly moving too, a vast space of exchange. It has played a vital role in maintaining Earth’s homeostasis, enabling the emergence of biodiverse life and human civilisation.

Phytoplankton are crucial because they form the base of the aquatic food web and produce O2 through photosynthesis. This plant life helps the oceans generate 50% of the world’s O2, absorb 25% of CO2 emissions and capture 90% of excess heat caused by Greenhouse Gases.

So the oceans are our lungs and our biggest carbon sink, a vital buffer against worsening climate impacts.

Water is openness, possibility, porosity, flowingness, a milieu for life, essential for the commons and community.

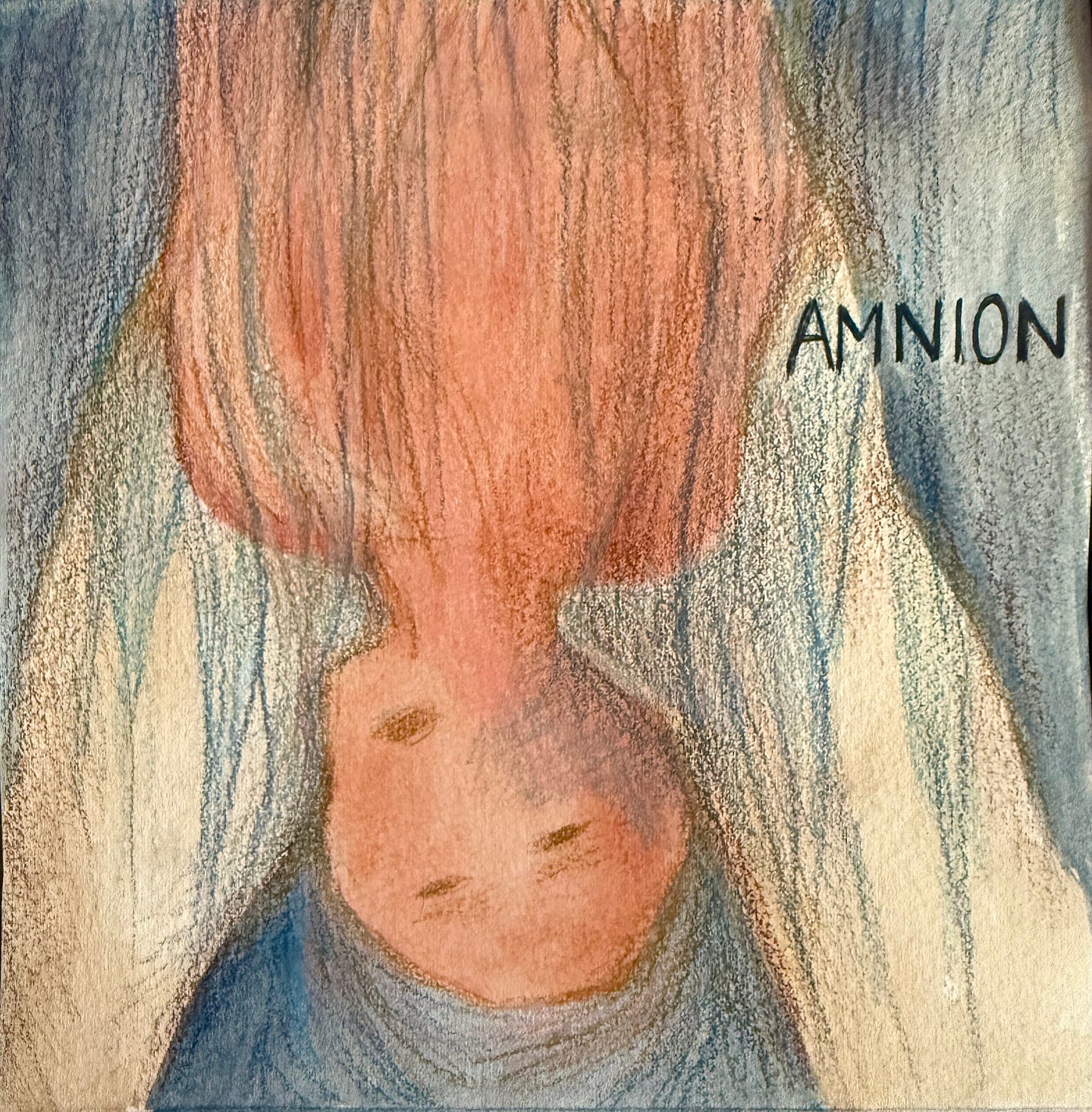

“Water that I breathe in becomes a constituent that makes up most of my body. Water that I breathe out becomes part of someone else’s body. Water travels the world over, moving easily through land, air, soil, rock and bodies. It might take a long time, but Nibi [water] always escapes the container.” Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, Theory of Water

HOW DO YOU TAKE IN THE TRUTH?

The balance of O2 and CO2 that has enabled a stable climate for human civilisation is threatened. The oceans are becoming acidic, hot and polluted from fossil fuel emissions, plastic and chemical pollution and warming temperatures. The green of phytomass and the vibrant colours of coral reefs are turning to grey, these colours replaced by islands of plastic waste. The ocean’s life can’t absorb as much CO2 as it used to, and all the while these emissions are rising, partly due to increasing wildfires.

Whales are falling silent as they are too hungry to sound their far-travelling songs. This is a detail of the big pattern of cascading impacts that hits deep and rough when we can take it all in and believe it. It’s hard to grasp because it involves uncertainty. It’s uncertain that biodiverse life and human civilisation can survive the onslaught of harms to the biosphere.

Timothy Lenton, a climate systems scientist, says critical Earth systems like the polar ice sheets, permafrost, and Atlantic Ocean circulation are nearing or have passed irreversible thresholds. He says the more scientists study this, the closer these thresholds appear, and that past assessments were too optimistic. This is overwhelming, and it feels impossible. Seeing so much trouble can make it very hard to look beyond the present day, to imagine how much better life can be. The overwhelm triggers us to seek pleasure or blame, immediate rewards, and to deny what we hear.

Yet, we are witnessing the creep of worse conditions. People are sick from pollution, overheated, fleeing drought, losing homes to fire and flood. Children are in bomb-panic right now somewhere. Horses are fleeing wildfires.

Why do so many of us deny the knowledge of our bodies and the truth of what we are witnessing? Don’t we all already get our nested enmeshment in life? Isn’t it a rich truth that resonates with our inherited wisdom, that taps into our self-knowing as animals dependent on air, water, food, peace and shelter?

If we allowed our perceptions to expand, perhaps to be like whales absorbing truths constantly through gills or wide open mouths, would we be capable of the right response?

Maybe if we deepen our framing of time and who we recognise as our ancestors? Humans emerged from and depend upon millennia of symbiosis of trillions of organisms. We are not supreme above other forms of life, although our distinctive powers, technologies and populousness do make us crucial actors for planetary health.

This knowing is both material and awe-inspiring. It is sacred knowledge, graspable and deep at the same time. The thin veil that conceals this knowledge can be torn by acknowledging the Earth itself as our deep-time living ancestor, by becoming guardians of the remaining parts of the Earth, like rivers or forests, that host the feeling bodies we live alongside, helping those feeling bodies as often as we can.

By caring for bodies that are not human, I don’t mean we should care less about our fellow humans. Our fates are all tied up together. 3.6 billion people live in areas highly vulnerable to climate impacts. Water is at the heart of this.

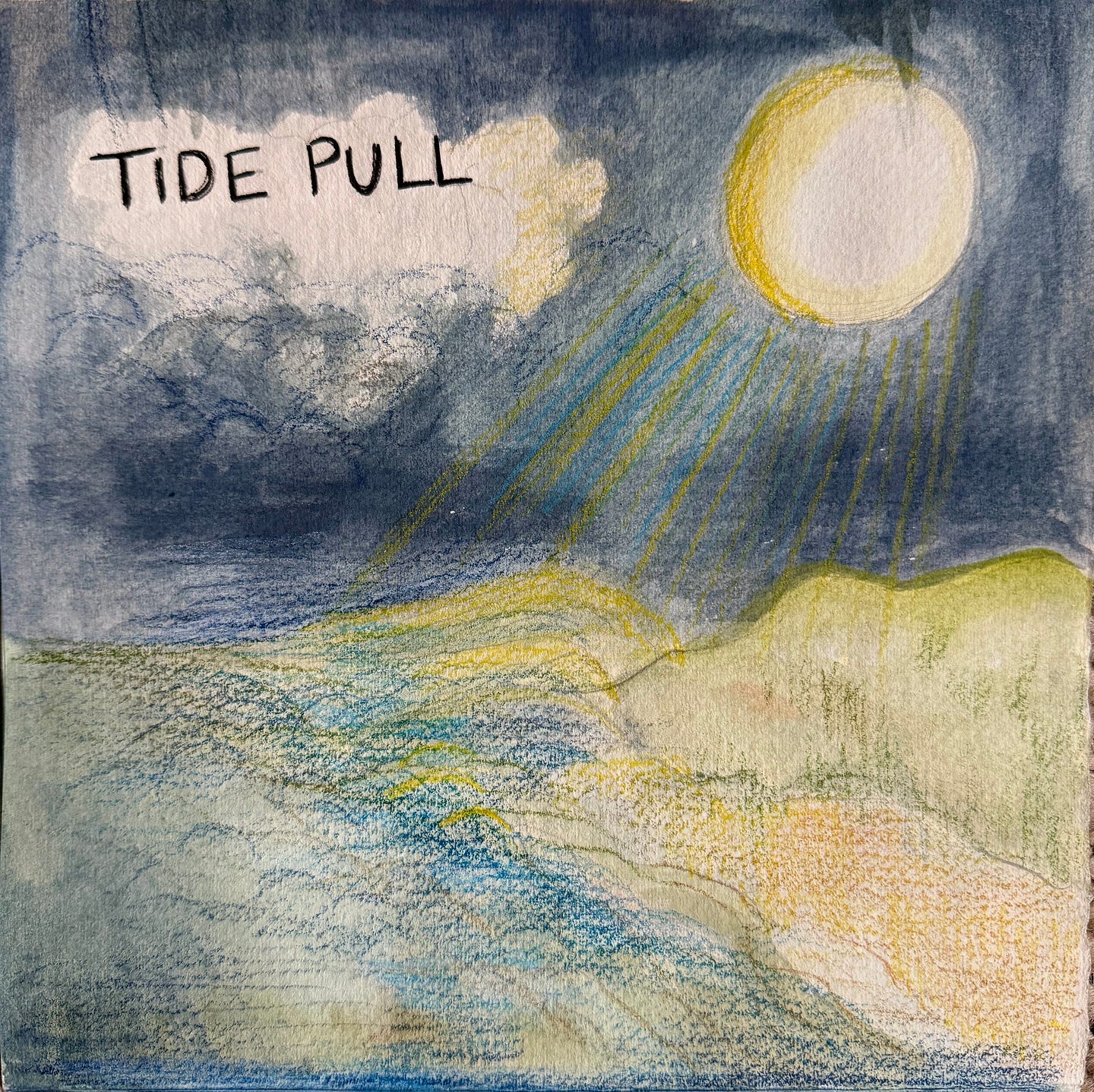

The heat absorbed into oceans has disrupted currents and weather patterns. 97% of extreme weather incidents are caused by water in the wrong place, so there are chaotic swings between heavy rainfall or drought, and heavier storms.

Women in particular, in the most affected places, have heavy burdens in obtaining water, growing food and caring for each other as conditions worsen.

“The crops here were green in May when the others all around were brown with drought.” Harry Buscall, Wild Ken Hill, on the impacts of rewilding and regenerative farming

ARE YOU SAFE HERE?

Here in Norfolk, we feel relatively safe when we see widespread fires in Brazil or rivers gushing down mountains in Pakistan. But Europe is the fastest-warming continent in the world. In the UK, we depend on food grown in areas — like Norfolk — where climate impacts are reducing crop yields. The rainfall has always been low here, so drought hits hard, and wildfires are an increasing risk on our heathlands, reedbeds and farmlands with degraded soil.

Also, this is among the most vulnerable UK counties because so much of it is low-lying and its coastal cliffs and dunes are easily eroded. Threatened landscapes include the historic town centre of King’s Lynn and the wider Fens.

In the face of threats, we easily turn to ‘magical thinking’ — to silver bullets and divine interventions and the power of hope. It’s a part of our heritage to do this. Norfolk fishing communities used to perform symbolic actions and tell stories to assuage the sea fairies, to quell the dangerous seas and storms. King’s Lynn women and girls would go to the quay when the boats departed, and then return on the high tide. They carried with them their house keys, and turned these in an outward motion on the outward journey, and inward on their return, keeping an invisible connection with those at sea. This was both a recognition that there are greater forces in nature that only magic can hope to reckon with, and part of the human story of ‘power over’ the landscape.

This ‘power over’ the landscape was, in many ways, effective for millennia. The archaeologist Francis Pryor, in ‘The Fens’, touches on discoveries of the origins of livestock farming around 3700 BC. The land was significantly altered with and for tamed animals, but land-shaping methods were in balance with forager-stewardship. That is, until the enclosure and conversion of the Fens into a breadbasket, described by James Boyce in ‘Imperial Mud: The Fight for the Fens’.

The drainage and shrinkage of land to below sea level was part of the damage to the natural management of the Fens. Boyce describes the resistance by Fen Tigers who wanted to protect their wild ‘mirescape’ for their traditional diet of eels, fish and wildfowl and materials like reeds.

So, here is a conundrum in the matter of time — that livestock farming and grain cultivation began 5700 years ago, but also a fight to protect the means for a forager economy from 1450 to 1850.

People needed the sovereignty of access to land, as indigenous stewards and for their nutrition. This is true today, even more so as climate impacts hit food supplies worldwide.

We’re not safe, but we can be safer, and this can start by being more connected to our land and water.

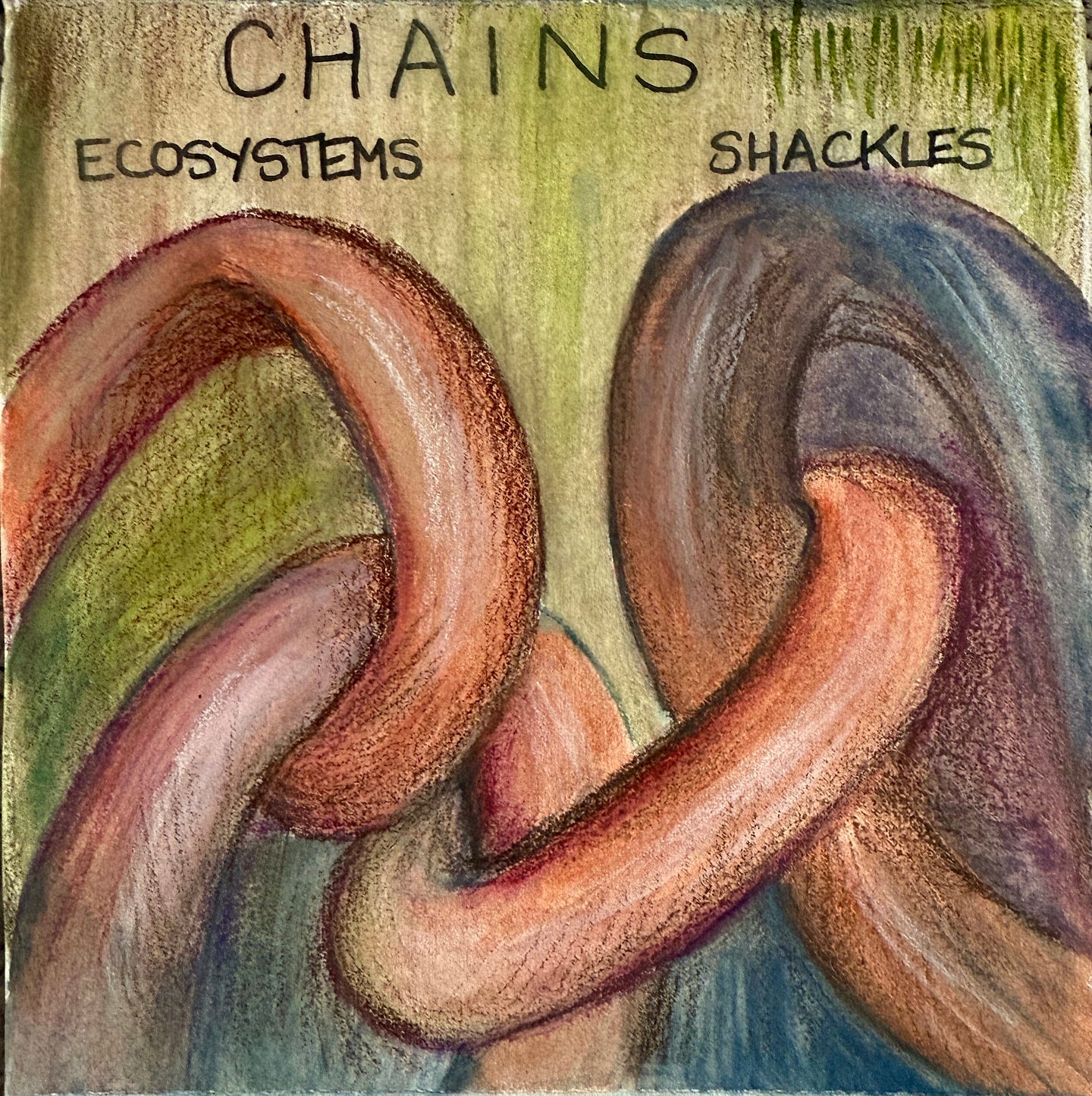

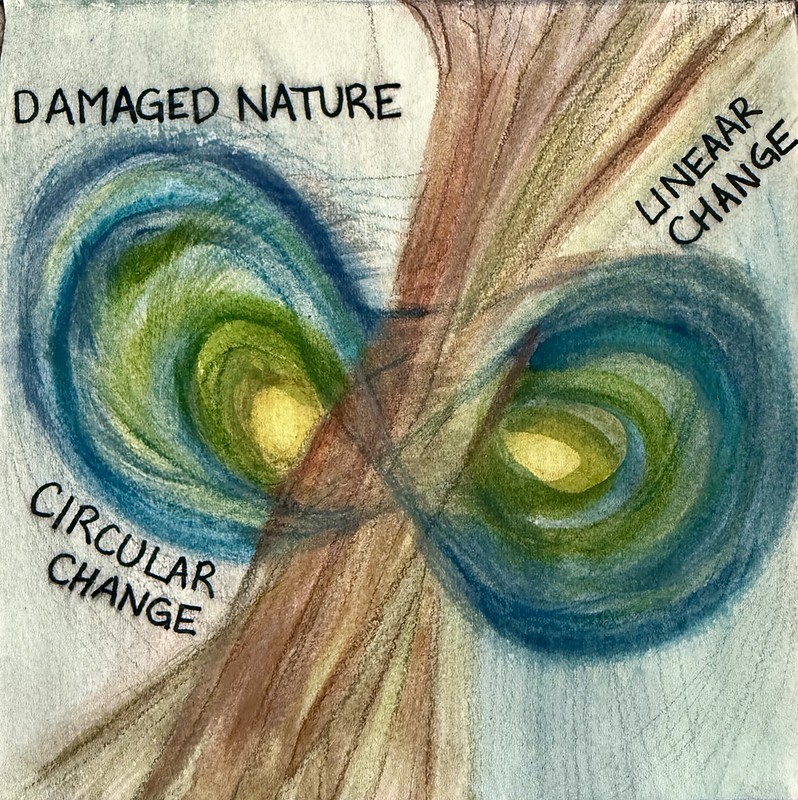

“There are two types of change, circular change like seasonal migrations, and linear change, like climate disruption.” Nick Acheson

WHERE IS THE HOPE?

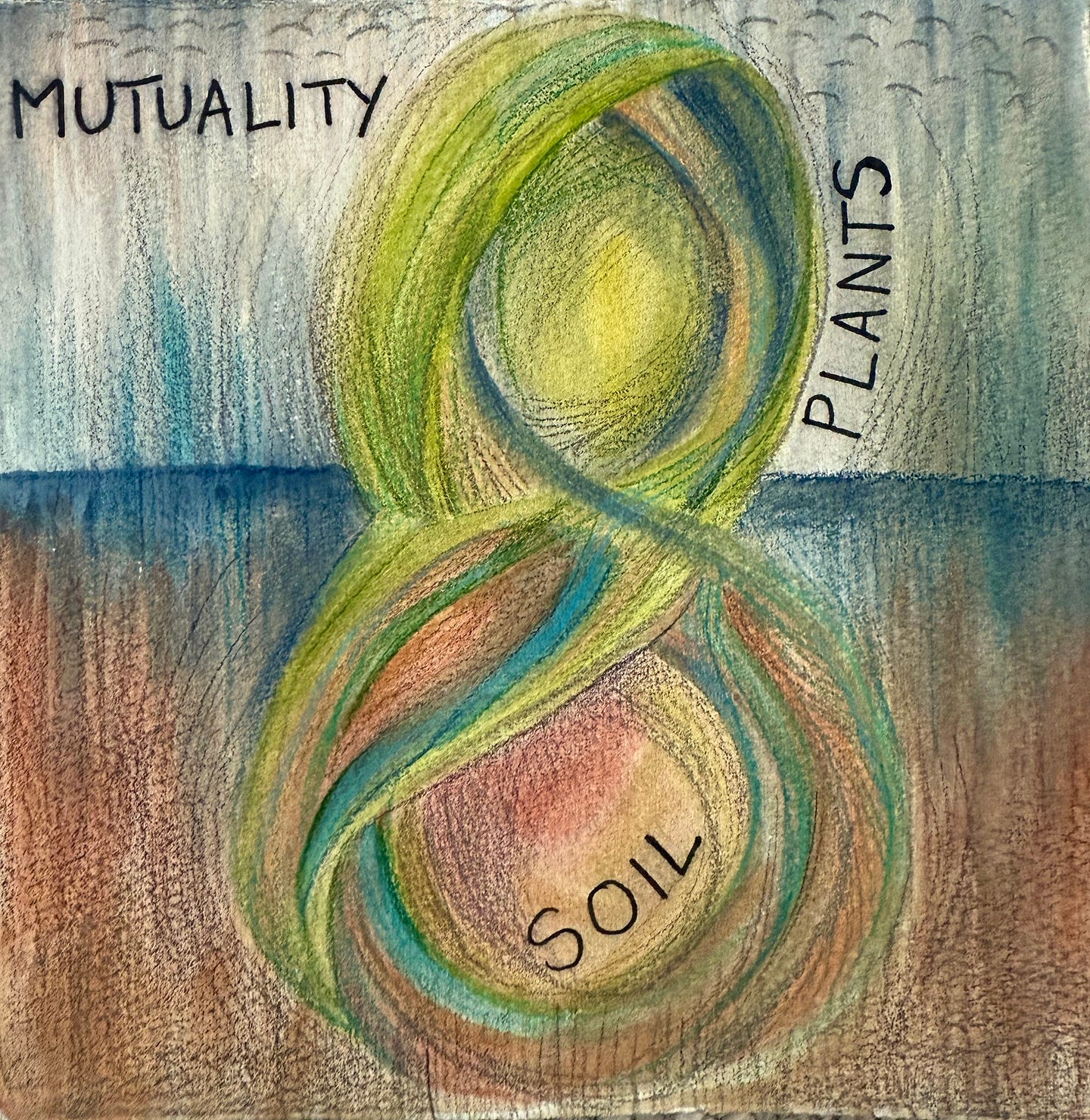

Gustav Metzger, an artist who lived in King’s Lynn, invited us to remember nature. If we re-member nature, we put its members or parts back together again. We can restore the mutuality between plants and soil, micro-organisms and larger animals, and the balance of Earth systems.

Hope is in water, seeing it as sacred, restoring the ghost ponds and re-wriggling the rivers.

Hope is in the awesome diversity and patterns of life. Hope is in creating refuges for wild lives.

Hope is in forming communities that aim to be resilient and regenerate land for future generations.

WHAT CAN YOU DO?

Acknowledge the Earth Crisis. The rapid acceleration of Global Warming is the most important environmental issue in human history. It is a ‘threat multiplier’ to all the other areas of ecological overshoot and social shortfall.

Understand that a metastatic fever has taken over. The growth narrative is on overdrive, and the extractive lobbies and extremely wealthy are driving an extremely destructive version of capitalism.

Find your contribution. It is not just a technical issue, or a matter of slight adjustments to your living habits. The Crisis can be tackled from many angles.

It must be tackled with a broad awareness of ecology, materials, politics, culture and psychology. The best tactics to reduce emissions also reduce other forms of pollution and harm, including racism and wars.

Speak out, knowing that most people and most experts are with you. 89% of people worldwide are climate-concerned and want to see increased political action — but most assume that others don’t feel the same. Scientists are with you. They are united and have proven that climate change is real, happening now, extremely serious and caused by industrial & agricultural activities. Lawyers are with you. The International Court of Justice’s unanimous opinion states that climate action is now a legal duty.

Combine with others (supporting existing groups) and plan action at the highest point of leverage you can manage. For example, take legal action against companies and states breaking the law on climate. Help your organisation or company crank up from a soft sustainability plan to an Earth Crisis response and responsibility strategy. This means a rigorous crafting of interventions on these four dimensions:

ENVIRONMENTAL: Stop doing the most harmful things. Work to restore and protect more-than-human life. Tackle climate change as a threat multiplier, among other impacts.

PEOPLE: Engage individuals as agents of change. Tend to people, tackling inequalities and ensuring that people’s needs are met as impacts unfold.

LOCAL: Integrate imagination, the arts and heritage stewardship into your plans. Support people to imagine better futures. Flip the story of domination, for the benefit of people and planet in places.

GLOBAL: Activate change. Support and don’t suppress initiatives that tackle territorial conflict, wealth hoarding, authoritarianism, and collapsing ecosystems. Make interventions in your personal lives and locally, while keeping an eye on global and systemic ripples of change.